Scaling of an antibody validation procedure enables quantification of antibody performance in major research applications

Abstract

Antibodies are critical reagents to detect and characterize proteins. It is commonly understood that many commercial antibodies do not recognize their intended targets, but information on the scope of the problem remains largely anecdotal, and as such, feasibility of the goal of at least one potent and specific antibody targeting each protein in a proteome cannot be assessed. Focusing on antibodies for human proteins, we have scaled a standardized characterization approach using parental and knockout cell lines (Laflamme et al., 2019) to assess the performance of 614 commercial antibodies for 65 neuroscience-related proteins. Side-by-side comparisons of all antibodies against each target, obtained from multiple commercial partners, have demonstrated that: (i) more than 50% of all antibodies failed in one or more applications, (ii) yet, ~50–75% of the protein set was covered by at least one high-performing antibody, depending on application, suggesting that coverage of human proteins by commercial antibodies is significant; and (iii) recombinant antibodies performed better than monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies. The hundreds of underperforming antibodies identified in this study were found to have been used in a large number of published articles, which should raise alarm. Encouragingly, more than half of the underperforming commercial antibodies were reassessed by the manufacturers, and many had alterations to their recommended usage or were removed from the market. This first study helps demonstrate the scale of the antibody specificity problem but also suggests an efficient strategy toward achieving coverage of the human proteome; mine the existing commercial antibody repertoire, and use the data to focus new renewable antibody generation efforts.

eLife assessment

Antibodies are some of the most important tools in biomedical research. However, their quality and specificity vary significantly. This fundamental study provides important guidelines for how the quality of an antibody should be assessed and recorded and provides compelling data on the selected antibodies. This paper will be of interest to researchers working in experimental cell biology.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.91645.2.sa0eLife digest

Commercially produced antibodies are essential research tools. Investigators at universities and pharmaceutical companies use them to study human proteins, which carry out all the functions of the cells. Scientists usually buy antibodies from commercial manufacturers who produce more than 6 million antibody products altogether. Yet many commercial antibodies do not work as advertised. They do not recognize their intended protein target or may flag untargeted proteins. Both can skew research results and make it challenging to reproduce scientific studies, which is vital to scientific integrity. Using ineffective commercial antibodies likely wastes $1 billion in research funding each year.

Large-scale validation of commercial antibodies by an independent third party could reduce the waste and misinformation associated with using ineffective commercial antibodies. Previous research testing an antibody validation pipeline showed that a commercial antibody widely used in studies to detect a protein involved in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis did not work. Meanwhile, the best-performing commercial antibodies were not used in research. Testing commercial antibodies and making the resulting data available would help scientists identify the best study tools and improve research reliability.

Ayoubi et al. collaborated with antibody manufacturers and organizations that produce genetic knock-out cell lines to develop a system validating the effectiveness of commercial antibodies. In the experiments, Ayoubi et al. tested 614 commercial antibodies intended to detect 65 proteins involved in neurologic diseases. An effective antibody was available for about two thirds of the 65 proteins. Yet, hundreds of the antibodies, including many used widely in studies, were ineffective. Manufacturers removed some underperforming antibodies from the market or altered their recommended uses based on these data. Ayoubi et al. shared the resulting data on Zenodo, a publicly available preprint database. The experiments suggest that 20-30% of protein studies use ineffective antibodies, indicating a substantial need for independent assessment of commercial antibodies.

Ayoubi et al. demonstrated their side-by-side antibody comparison methods were an effective and efficient way of validating commercial antibodies. Using this approach to test commercial antibodies against all human proteins would cost about $50 million. But it could save much of the $1 billion wasted each year on research involving ineffective antibodies. Independent validation of commercial antibodies could also reduce wasted efforts by scientists using ineffective antibodies and improve the reliability of research results. It would also enable faster, more reliable research that may help scientists understand diseases and develop new therapies to improve patient’s lives.

Introduction

Antibodies are critical reagents used in a range of applications, enabling the identification, quantification, and localization of proteins studied in biomedical and clinical research. The research enterprise spends significantly on the ~1.6 M commercially available antibodies targeting ~96% of human proteins (Bandrowski et al., 2023). Unfortunately, a significant percentage of these antibodies do not recognize the intended protein or recognize the protein but also recognize non-intended targets, with estimates that $0.375 to $1.75 billion is wasted yearly on non-specific antibodies (Baker, 2015; Bradbury and Plückthun, 2015; Voskuil et al., 2020). Perhaps worse, the use of poor-quality antibodies is a major factor in the scientific reproducibility crisis (Bradbury and Plückthun, 2015; Voskuil et al., 2020; Baker, 2020). With tens to hundreds of antibodies available for any given protein target, it is difficult for antibody users to select the best performing antibody (Voskuil, 2014), and a growing number of cases reveal that depending on previously published antibodies is not a reliable method to assess their performance (Laflamme et al., 2019; Sato et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023; Sicherre et al., 2021; Haytural et al., 2019; Virk et al., 2019). Academic and industry scientists aspire to have at least one, and ideally more, potent, selective and renewable antibody for each human protein for each of the most common applications (Marx, 2020). Unfortunately, there is no agreed-upon mechanism to determine, validate or compare antibody performance and there are multiple strategies for antibody validation (Uhlen et al., 2016), with unequal scientific value. Most information on how commercial antibodies perform is anecdotal. It is thus difficult to assess progress toward the objective of well-validated antibodies for each human protein, or to design a strategy to accomplish this aim.

We sought to address this issue by developing optimized protocols to assess antibody specificity in the three most common uses of antibodies in biomedical research laboratories; Western blot (WB), immunoprecipitation (IP), and immunofluorescence (IF). We used these protocols to test antibodies against a variety of neuroscience targets, chosen by funders, to predict requirements for the larger goal of coverage of an entire mammalian proteome. The optimal antibody testing methodology is largely settled; using an appropriately selected wild type cell and an isogenic CRISPR knockout (KO) version of the same cell as the basis for testing, yields rigorous and broadly applicable results (this study, as well as Laflamme et al., 2019; Ellis et al., 2023; Davies et al., 2013). However, the cost of antibody characterization using engineered KO cells is higher than that of other methods, mainly because of the cost of custom edited cells. Commercial antibody suppliers support a large and diverse catalogue of products, with most antibody products generating <$5000 in total sales, far less than the costs of KO-based validation, estimated at $25,000. While leading companies are increasingly assessing antibody performance, it is exceedingly difficult, and cost restrained, to properly characterize all their products. Even when available, high-performing antibodies may remain hidden within the millions of reagents of unknown quality.

To begin the process of large-scale antibody validation and to provide a large enough dataset to allow for more accurate estimates of the work and financing required to complete such a project, we began with the human proteome. We created a partnership of academics, funders, and commercial antibody manufacturers, including 10 companies representing approximately 27% of antibody manufacturing worldwide. For each protein target, we tested commercial antibodies, provided from various manufacturers, in parallel using standardized protocols, agreed upon by all parties, in WB, IP, and IF applications. All data are shared rapidly and openly on ZENODO, a preprint server. We have tested 614 commercially available antibodies targeting 65 proteins, and found that approximately two thirds of this protein set was covered by at least one high-performing antibody, and half was covered by at least one high-performing renewable antibody, suggesting that coverage of human proteins by high-performing antibodies is significant. This sample is large enough to observe several trends in antibody performance across various parameters and estimate the scale of the antibody liability crisis.

Results

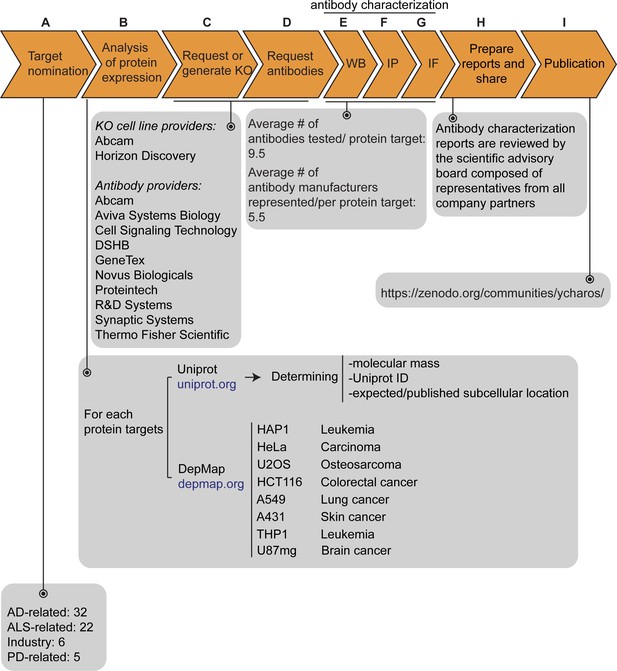

Assembling KO cell lines and antibodies

Our initiative has thus far validated antibodies for 65 protein targets, which were chosen by disease charities, academia, and industry without consideration of antibody coverage. The list is comprises 32 Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-related proteins that were community-nominated through an NIH-funded project on dark AD genes (https://agora.adknowledgeportal.org/), 22 proteins nominated within the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) Reproducible Antibody Platform project, 5 Parkinson’s disease (PD)-linked proteins nominated by the Michael J. Fox Foundation, and 6 proteins nominated by industry (Figure 1A). Within the 65 target proteins, 56 are predicted intracellular and 9 are predicted secreted. The description of each protein target is indicated in Figure 1—source data 1.

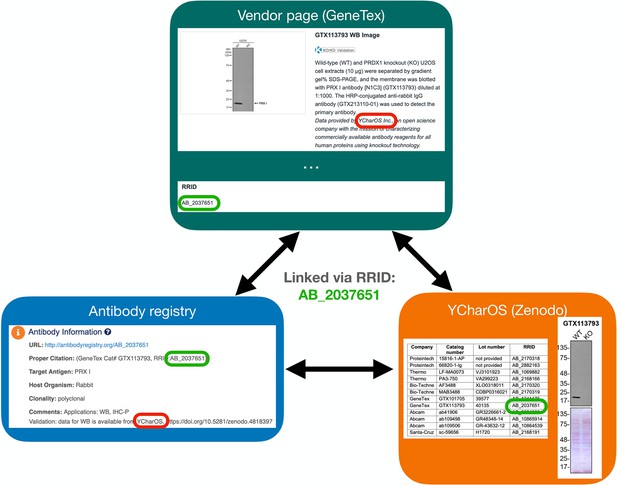

Antibody characterization platform.

(A) The funders of the targets analyzed in this study and the number of targets proposed by each are indicated. (B) Bioinformatic analyses of nominated proteins using Uniprot to determine their molecular mass, unique Uniprot ID and published/expected subcellular distribution. In parallel, analyses of the Cancer Dependency Map (‘DepMap’) portal provided RNA sequencing data for the designated target, which guided our selection of cell lines with adequate expression for the generation of custom KO cell lines. A subset of cell lines amenable for genome engineering were prioritized. (C) Receive relevant KO cell lines or generate custom KO lines and (D) receive antibodies from manufacturing partners. All contributed antibodies were tested in parallel by (E) WB using WT and KO cell lysates ran side-by-side, (F) IP followed by WB using a KO-validated antibody identified in (E) and by (G) IF using a mosaic strategy to avoid imaging and analysis biases. (H) Antibody characterization data for all tested antibodies were presented in a form of a protein target report. All reports were shared with participating companies for their review. (I) Reviewed reports were published on ZENODO, an open access repository. ALS-RAP=amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-reproducible antibody platform, AD = Alzheimer’s disease, MJFF = Michael J. Fox Foundation. KO = knockout cell line.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Description of the 65 nominated target proteins.

List of all nominated proteins for which an antibody characterization report was generated. The list includes the corresponding protein name, gene name, Uniprot ID, expected subcellular distribution, number of articles referring to the protein itself, the total number of antibodies tested, the number of renewable antibodies tested, the number of companies that have provided antibodies, the cell line background used to generate a KO line, the RNA level – units are log2(TPM +1) and the DOI referring to the antibody characterization report uploaded on ZENODO or to another publication platform.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/91645/elife-91645-fig1-data1-v1.xlsx

The proteins were searched to determine the Uniprot identifier, the predicted molecular mass, and whether the protein is secreted or intracellular (Figure 1B). Our strategy was predicated on identifying a parental cell line that expressed sufficient levels of the target protein to be detected by an antibody with a binding affinity of 1–50 nM. To identify candidate lines, we searched the Cancer Dependency Map Portal (DepMap) using the ‘Expression 22Q1’ database, which houses the RNA-level analysis of >1800 cancer cell lines (Ghandi et al., 2019; Figure 1B). After our initial experience with a few dozen targets comparing RNA expression and the ability to detect a clear signal, we selected 2.5 log2(TPM +1) as an RNA-level threshold to select a candidate cell line to create a KO. Among the cell lines showing expression above this level, we prioritized a group of 8 common cell line backgrounds representing different cell/tissue types because their doubling time is short, and they are amenable to CRISPR-Cas9 technology (Figure 1B). These 8 cell lines were used in 62 out of the 65 antibody characterization studies (Figure 1—source data 1).

After identifying candidate cell lines for each target, we either obtained KO lines from our industry consortium partners or generated them in-house (Figure 1C). Antibodies were provided from antibody manufacturers, who were responsible for selecting antibodies to be tested from their respective catalogs (Figure 1D). Most antibody manufacturers prioritized renewable antibodies. The highest priority was given to recombinant antibodies as they represent the ultimate renewable reagent (Marx, 2020) and have advantages in terms of adaptability, such as switching IgG subclass (Andrews et al., 2019) or using molecular engineering to achieve higher affinity binding than B-cell generated antibodies (Gray et al., 2020).

All available antibodies from all companies were tested side-by-side in parental and KO lines. The protocols used were established by our previous work (Laflamme et al., 2019) and refined in collaboration with antibody manufacturers. On occasion, our protocols differed from those the companies used in their internal characterization. All antibodies were tested for all three applications (except that secreted proteins were not tested in IF), independent of the antibody manufacturers’ recommendations. We received on average 9.5 antibodies per protein target contributed from an average of five different antibody manufacturers (Figure 1E, F and G). Companies often contributed more than one antibody per target (Figure 1—source data 1).

Antibody and cell line characterization

For WB, antibodies were tested on cell lysates for intracellular proteins or cell media for secreted proteins (Figure 1E). For 55/65 of the target proteins, we identified one or more antibodies that successfully immunodetected their cognate protein, identifying well-performing antibodies and validating the efficacy of the KO lines. For the remaining nine targets, we identified at least one specific, non-selective antibody that detects the cognate protein by WB, but also recognizes unrelated proteins, that is, non-specific bands not lost in the KO controls. All 614 antibodies were tested by IP on non-denaturing cell lysates for intracellular proteins or cell media for secreted proteins, using WB with a successful antibody from the previous step to evaluate the immunocapture (Figure 1F). All antibodies against intracellular proteins were tested for IF using a strategy that imaged a mosaic of parental and KO cells in the same visual field to reduce imaging and analysis biases (Figure 1G).

For each protein target, we consolidated all screening data into a report, which is made available without restriction on ZENODO, a data-sharing website operated by CERN. On ZENODO, all 65 reports are gathered under the Antibody Characterization through Open Science (YCharOS) community: https://ZENODO.org/communities/ycharos/ (Figure 1I). Prior to release, each antibody characterization report underwent technical peer review by a group of scientific advisors from academia and industry (Figure 1H).

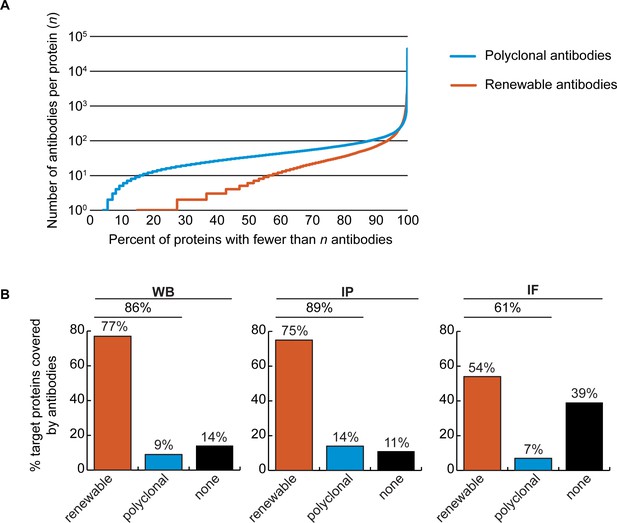

Coverage of human proteins by renewable antibodies

The Antibody Registry (https://www.antibodyregistry.org, RRID:SCR_006397) indicates that there are ~1.6 million antibodies covering ~96% of human proteins (Bandrowski et al., 2023), with 53% covered by at least five renewable antibodies (Figure 2A, Figure 2—source data 1). Approximately 21% of human proteins are covered by only one or two renewable antibodies, and ~15% have no renewable antibodies available (Figure 2A). In our set of 65 proteins, and from the manufacturers represented, 49 were covered by at least 3 renewable antibodies, 15 by 1 or 2 renewable antibodies, and 1 was not covered by any renewables (Figure 1—source data 1).

Analysis of human protein coverage by antibodies.

(A) Cumulative plot showing the percentage of the human proteome that is covered by polyclonal antibodies (blue line) and renewable antibodies (monoclonal +recombinant; orange line). The number of antibodies per protein was extracted from the Antibody Registry database. (B) Percentage of target proteins covered by minimally one renewable successful antibody (orange column) or covered by only successful polyclonal antibodies (blue column) is shown for each indicated applications using a bar graph. Lack of successful antibody (‘none’) is also shown (black column).

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Number of antibodies per human protein.

The Antibody Registry was queried with a set of Uniprot-derived protein names representing 16,262 human proteins. The number of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies (representing recombinant and mouse monoclonal antibodies) that match the protein list is shown.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/91645/elife-91645-fig2-data1-v1.xlsx

We found a well-performing renewable antibody for 50 targets in WB (Figure 2B, left bar graph), for 49 targets in IP (Figure 2B, middle bar graph), and for 30 targets in IF (Figure 2B, right bar graph). For some proteins lacking coverage by renewable antibodies or lacking successful renewable antibodies, well-performing polyclonal antibodies were identified (Figure 2B). Some proteins were not covered by any successful antibodies depending on application; notably ~40% of our protein set lacked a successful antibody for IF (Figure 2B, right bar graph).

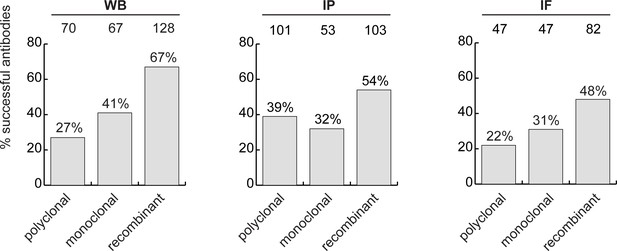

Recombinant antibody performance

The antibody set constituted 258 polyclonal antibodies, 165 monoclonal antibodies and 191 recombinants. For WB, 27% of the polyclonal antibodies, 41% of the monoclonal antibodies and 67% of the recombinant antibodies immunodetected their target protein (Figure 3, left bar graph). For IP, trends were similar: 39%, 32% and 54% of polyclonal, monoclonal and recombinants, respectively (Figure 3, middle bar graph). For IF, we tested 529 antibodies against the set of intracellular proteins; 22% of polyclonal antibodies, 31% of monoclonal antibodies, and 48% of recombinant antibodies generated selective fluorescence signals in images of parental versus KO cells (Figure 3, right bar graph). Thus, recombinant antibodies are on average better performers than polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies in each of the applications. It should be noted that recombinant antibodies are newer protein reagents compared to polyclonal and monoclonal hybridomas, and their superior performance could be a consequence of enhanced internal characterization by the commercial suppliers.

Analysis of antibody performance by antibody types.

The percentage of successful antibodies based on their clonality is shown using a bar graph, for each indicated application. The number of antibodies represented in each category is indicated above the corresponding bar.

Our analyses also inform the characterization pipelines to use for newly generated renewable antibodies. Currently, it is common to use WB as the initial screen (Lund-Johansen and Browning, 2017). However, we find that success in IF is the best predictor of performance in WB and IP (Figure 3—figure supplement 1).

Optimizing an antibody characterization strategy

While the parental versus KO method is the consensus superior method for antibody validation (Laflamme et al., 2019; Ellis et al., 2023; Davies et al., 2013; Lutz et al., 2022), not all antibodies on the market are characterized this way, largely due to cost and the range of alternative methods (Uhlen et al., 2016). To assess if the cost of KO characterization is justified, we compared the performance of antibodies in our dataset to the performance predicted by the characterization methods used by the companies. In all, 578 of the 614 antibodies tested were recommended for WB by the manufacturers. Of these, 44% were successful, 35% were specific but non-selective, and 21% failed (Figure 4—figure supplement 1, left bar graph). Most antibodies are not recommended for IP by the suppliers, perhaps because they are not tested. Of 614 antibodies, 143 were recommended for IP, and 58% enriched their cognate target from cell extracts. Interestingly, of the 471 remaining antibodies that had no recommendation for IP, 37% were able to enrich their cognate antigen (Figure 4—figure supplement 1, middle bar graph). In this regard, the manufacturers are not sufficiently recommending their successful products. Of the 529 antibodies tested in IF, 293 were recommended for this application by the suppliers and 236 were not. Only 39% of the antibodies recommended for IF were successful (Figure 4—figure supplement 1, right bar graph).

We next investigated if antibody validation strategies have equal scientific value. Broadly, antibodies are characterized using genetic approaches, which exploit KO or knockdown (KD) samples as controls, or using orthogonal approaches, which rely on known information about the target protein of interest as a correlate to validate performance. For WB, 61% of antibodies were recommended by manufacturers based on orthogonal approaches, 30% based on genetic approaches and 9% using other strategies. For IF, 83% of the antibodies were recommended based on orthogonal approaches, 7% using genetic approaches and 10% using other strategies (Figure 4A). For WB, 80% of the antibodies recommended by the manufacturers based on orthogonal strategies and 89% of antibodies recommended based on genetic strategies could detect the intended target protein (Figure 4B, left bar graph). For IF, 38% of the antibodies recommended by the manufacturers based on orthogonal strategies were confirmed using KO cells as controls. Of the 20 antibodies validated by the manufacturers for IF on the basis of genetic strategies, we confirmed the performance of 16 (80%) (Figure 4B, histogram right). Of the four antibodies that failed in our hand, one has already been withdrawn from the market by the manufacturer. Thus, while orthogonal strategies are somewhat suitable for WB, genetic strategies generate far more robust characterization data for IF.

Scientific value of antibody characterization methods and research usage.

(A) Percentage of antibodies validated by suppliers using one of the indicated methods for WB or IF showed using a bar graph with stacked columns. The percentage corresponding to each section of the bar graph is shown directly in the bar graph. Orthogonal = orthogonal strategies, genetic = genetic strategies. (B) Percentage of successful (light gray), specific, non-selective (dark gray-only for WB) and unsuccessful (black) antibodies according to the validation method used by the manufacturer for WB and IF as compared to the KO strategy used in this study. Data are shown using a bar graph with stacked columns. The percentage corresponding to each section of the bar graph is shown directly in the bar graph. The number of antibodies analyzed corresponding to each condition is shown above each bar. (C) Percentage of publications that used antibodies that successfully passed validation (correct usage) or to antibodies that were unsuccessful in validation (incorrect usage) showed using a bar graph with stacked columns. The number of publications was found by searching CiteAb. The percentage corresponding to each section of the bar graph is shown in the bar graph and the number of publications represented in each category is shown above the corresponding bar. (D) Percentage of publications that used an unsuccessful antibody for IF from (C) that provided validation data for the corresponding antibodies. Data is shown as a bar graph. The number of publications represented in each category is shown above the corresponding bar.

From a total of 409 antibodies that presented conflicting data between our characterization data and antibody supplier’s recommendations, the participating companies have withdrawn 73 antibodies from the market and changed recommendations for 153 antibodies (Figure 4—figure supplement 2). In turn, high-quality antibodies are being promoted. We expect to see additional changes and an overall improvement in the general quality of commercial reagents as more antibody characterization reports are generated.

Antibodies and reproducible science

The availability of renewable, well-characterized antibodies would be expected to enhance the reproducibility of research. To assess the bibliometric impact of underperforming antibodies, we used the reagent search engine CiteAb (https://www.citeab.com/) to quantify how antibodies in our dataset have been used in the literature. We identified 2010 publications that employed one of the 180 antibodies we tested for WB. Of those, 69% used a well-performing antibody that specifically immunodetected its target protein by WB, while 31% used an antibody unsuccessful in our protocol (Figure 4C). For IP, 105 publications employed 41 of our tested antibodies while 65% of these used a well-performing antibody but 35% employed an antibody unable to immunocapture its target protein (Figure 4C). For IF, we found 548 publications that employed 80 of the antibodies we tested. Of these publications, 22% used an antibody unable to immunolocalize its target protein (Figure 4C), with 88% containing no validation data (Figure 4D). If our results are representative, this suggests that 20–30% of figures in the literature are generated using antibodies that do not recognize their intended target, and that more effort in antibody characterization is highly justified.

A Research Resource Identification (RRID) was assigned to each of the 614 antibodies tested, indicated in each of the 65 antibody characterization reports available on ZENODO (Figure 5, bottom right image). Antibody characterization data generated by this organization are being disseminated by the RRID community and are directly connected through the Antibody Registry, or the RRID Portal (Figure 5, bottom left image) and participating antibody manufacturers’ websites (Figure 5, top image).

Discussion

Here, we present the analysis of a dataset of commercial antibodies as an assessment of the problem of antibody performance, and as a step toward a comprehensive and standardized ecosystem to validate commercial antibodies. We evaluated 614 antibodies against 65 human proteins side-by-side in WB, IP, and IF. All raw data are openly available (https://ZENODO.org/communities/ycharos/), identifiable on the RRID portal and on participating antibody manufacturers’ websites. Our studies provide an unbiased and scalable analytical framework for the representation and comparison of antibody performance, an estimate of the coverage of human proteins with renewable antibodies, an assessment of the scientific value of common antibody characterization methods, and they inform a strategy to identify renewable antibodies for all human proteins.

Our approach, developed in collaboration with manufacturers, and intended to be applied to entire proteomes, uses universal protocols for all tested antibodies in each application. Scientists use variants of such protocols, optimized for their protein of interest, which can have a major impact on antibody performance (Pillai-Kastoori et al., 2020; Piña et al., 2022; Marcon et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the process robustly identifies antibodies that fail to recognize their intended target, which becomes evident when other antibodies tested in parallel perform well. At a minimum, removal of these poorly performing products from the market will have significant impact in that hundreds of published papers report the use of such antibodies.

The impacts of poorly performing antibodies are well documented (Voskuil et al., 2020; Sato et al., 2021; Aponte Santiago et al., 2023; Freedman et al., 2016); our analyses provide insight into the magnitude of the problem. In our set of 65 proteins, we found that an average of ~12 papers per protein included use of an antibody that failed to recognize the intended protein target using our protocols. Scientists are not entirely to blame; dozens of antibodies can be used in a single study, often unrelated to the authors’ protein of interest. Genetic validation of every antibody used in a study remains a difficult, if not impossible task. In addition, even with our optimized protocol, the cost of characterizing antibodies for a single protein is estimated at ~$25,000 USD. And if each investigator performs such an analysis, there will be multiple overlapping validation of any given antibody. We estimate a cost of $50 million USD to characterize antibodies against all proteins in a proteome, considering parallelization and industrialization of the procedure. The costs mentioned exclude the expenses of antibodies and knockout cell lines. However, it should be noted that this estimated cost for validation is far below the predicted waste on bad antibodies, currently estimated at ~$1B/year (Voskuil et al., 2020). Thus, independent antibody characterization with openly published data, funded by various global organizations, is an important, if not essential, initiative that is certain to save large amounts of money and increase the quality and reproducibility of the literature. This study demonstrates the feasibility of such an initiative.

Life scientists tend to focus on a small subset of human proteins, leading to an imbalance between a small percentage of well-studied proteins, and a higher percentage of poorly characterized proteins (Carter et al., 2019). Our set of 65 funder-designated proteins is an unbiased sample, representative of the heterogeneity of knowledge of the human proteome; a search of the NIH protein database revealed that 15 proteins (23% of our protein sample) are well studied with more than 500 publications and 50 proteins (77% of our protein sample) have corresponding publications ranging from 37 to 498 (Figure 1—source data 1). Although we observed that there are more commercial antibodies available for the best-studied proteins (Figure 1—source data 1), an encouraging result of our work is that more than half of our protein targets are covered by well-performing, renewable antibodies for WB, IP and IF - including both well characterized and more poorly studied proteins. Within the antibodies we tested, we found a successful renewable antibody for WB for 77% of proteins (50/65), for IP for 75% of proteins (49/65) and for IF for 54% of proteins (30/56) examined. Extrapolation of our findings to the human proteome would suggest that it might be possible to identify well-performing renewable reagents for half the human proteome, including poorly characterized proteins, simply by mining commercial collections. Indeed, it is likely that the coverage is greater because our corporate partners only represent 27% of the antibody production worldwide.

The research market is heavily dominated by polyclonal antibodies, and their use contributes to reproducibility issues in biomedical research (Baker, 2015; Baker, 2020) and present important ethical concerns. From a scientific perspective, polyclonal antibodies suffer from batch-to-batch variation and are thus in conflict with the scientific community desire to use and provide only renewable reagents. From an ethical perspective, the generation of polyclonal antibodies requires large numbers of animals yearly (Gray et al., 2016). While recombinant antibodies may rely on the use of animals for the initiation of an antibody generation program, animal-free in vitro molecular strategies are also used for production, and to generate new batches of these antibodies (Gray et al., 2020). As of today, the uptake of recombinant antibodies by the scientific community has not been satisfactory. For example, while leading antibody manufacturers are converting top-cited polyclonal antibodies into recombinant antibodies and removing underperforming antibodies from their catalogues, polyclonals remain the most purchased. This situation has also been acknowledged by the EU Reference Laboratory for Alternatives to Animal Testing and a lack of understanding in the use of recombinant methods has been suggested by authors of a recent correspondence to the editors of Nature Biotechnology (Gray et al., 2020). One reason for this confusion could be the absence of large-scale performance data comparing the various antibody generation technologies. In our dataset, recombinant antibodies performed well in all applications tested, arguing there is no reason not to adopt the recombinant technology. Moreover, our study strongly supports the idea that future antibody generation programs should focus on recombinant technologies.

Our analysis of antibody performance indicates that success in IF is an excellent predictor of performance in WB and IP. Given that it is difficult to imagine a characterization pipeline dependent on IF, we suggest that using KO (or knockdown in the case of an essential gene) strategies to screen antibodies for the intended application will provide the most effective approach to identify selective antibodies. Currently, one of the main barriers to large-scale production of high-quality antibodies is the lack of availability of KO lines derived from cells that express detectable levels of each human protein. Creation of a broadly accessible biobank of bespoke KO cells for each human gene should be a priority for the community.

Our studies are rapidly shared via the open platform ZENODO, and selected studies were published on the F1000 publication platform (https://f1000research.com/ycharos). This data generation and dissemination is intended to benefit the global life science community, but its impact depends on the real-world uptake of the data. In addition, we recognize that antibodies are used in other protocols or in variations of our protocols that may yield important new or different outcomes. Posting of such information from users worldwide on open platforms will allow continued improvements to the data. Thus, we have partnered with the RRID Portal Community to improve our dissemination strategies. The Antibody Registry is a comprehensive repository of over 2.5 million commercial antibodies that have been assigned with RRIDs to ensure proper reagent identification (Bandrowski et al., 2023). Our data can be searched in the AntibodyRegistry.org and other portals that display this data such as the RRID.site portal and dkNet.org. The search term ‘ycharos’ will return all the currently available antibodies that have been characterized and searching for the target or the catalogue number of the antibody in any of these portals will also bring back the YCharOs information. In the RRID.site portal and dkNet there will also be a green star, tagging the antibodies to further highlight the contribution of YCharOS. The project is also being promoted through large international bioimaging networks including Canada BioImaging (CBI - https://www.canadabioimaging.org/), BioImaging North America (BINA - https://www.bioimagingnorthamerica.org/) and Global BioImaging (GBI - https://globalbioimaging.org/).

Overall, this project provides the global life sciences community with a tremendous resource for the study of human proteins and will result in significant improvements in rigour and reproducibility in antibody-based assays and scientific discovery.

Materials and methods

Data analysis

Request a detailed protocolPerformance of each antibody was retrieved from the corresponding ZENODO report or publication (Figure 1—source data 1), for WB, IP and IF, and analyzed following the performance criteria described in Table 1. Antibody properties, application recommendations and antibody characterization strategies were taken from the manufacturers' datasheets. Throughout the manuscript, renewable antibodies refer to monoclonal antibodies from hybridomas and to recombinant antibodies (monoclonal and polyclonal recombinant antibodies) generated in vitro.

Antibody performance criteria.

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Successful antibody for western blot | A successful primary antibody immunodetects the target protein, and the signal observed in the WT lysate is lost in the KO lysates (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). The antibody does not recognize other proteins under the conditions tested. |

| Specific, non-selective antibody for western blot | The primary antibody specifically recognizes the target protein, but also unrelated protein(s) (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). |

| Successful antibody for immunoprecipitation | Under the conditions used, a successful primary antibody immunocaptures the target protein to at least 10% of the starting material (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B). |

| Successful antibody for immunofluorescence | A successful primary antibody immunolocalizes the target protein by generating a fluorescence signal in WT cells that is at least 1.5-fold higher than the signal in KO cells (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C). Signal provided by such antibody staining can be easily distinguished from unspecific background and noise. |

For Figure 2A, the analysis of the antibody coverage of human proteins was performed as previously described (Bandrowski et al., 2023) and antibodies were divided into polyclonal and renewable categories.

To evaluate the number of citations corresponding to each tested antibody (Figure 4C), we searched CiteAb (between November 2022 and March 2023) and used the provided analysis of citations per application. We then searched for publications mentioning the use of a poorly performing antibody for IF. Publications were filtered by application (ICC, ICC-IF, and IF) and reactivity (Homo sapiens) on CiteAb (on July 2023), each publication being manually checked to confirm antibody and technique. This resulted in 112 publications, which were then assessed for characterization data (Figure 4D).

We asked participating antibody suppliers to indicate the number of antibodies eliminated from the market, and the number of antibodies for which there was a change in recommendation due to their evaluation of our characterization data (Figure 4—figure supplement 2).

The correlation of antibody performance between two applications were evaluated by the McNemar test, followed by the chi-square statistic (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). The number of antibodies was reported in each corresponding cell of the 2x2 contingency tables, and chi-square statistic was computed as follows: . The null hypothesis is pb = pc (where p is the population proportion). Note that these hypotheses relate only for the cells that assess change in status, that is cell b which contains the number of antibodies which passed application #2, but failed application #1, whereas cell c contains the number of antibodies which passed application #1, but failed application #2. The test measures the effectiveness of antibodies for one application (from fail to pass) against the other application (change from pass to fail). If pb = pc, the performance of one application is not correlated with the performance of another application, whereas if pb <or > pC, then antibody performance from one application can inform on the performance of the other application. The computed value is compared to the chi-square probability table to identify the p-value (degree of freedom is 1). The percentage of antibodies indicated in the double y-axis graph was computed by dividing the number of antibodies in the corresponding cell to the total number of antibodies (sum of cell a, b, c and d).

The number of articles corresponding to each human target protein was assessed by searching the NIH protein database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/) on May 4, 2023.

Resource information (alphabetical order)

Request a detailed protocol| Name of the resource | RRID | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody Registry | RRID:SCR_006397 | https://antibodyregistry.org |

| Cancer Dependency Map Portal (DepMap) | RRID:SCR_017655 | https://depmap.org/portal/ |

| CiteAb | RRID:SCR_009653 | https://www.citeab.com |

| F1000research (YCharOS Gateway) | - | https://f1000research.com/ycharos |

| NIH protein database | - | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/ |

| Universal Protein Resource (Uniprot) | RRID:SCR_002380 | https://www.uniprot.org/ |

| ZENODO (YCharOS community) | - | https://zenodo.org/communities/ycharos |

Data availability

All data generated and analysed during this study are included in the corresponding antibody characterization reports openly available on the ZENODO open data repository (links to ZENODO reports are provided in Figure 1—source data 1).

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Amyloid-beta precursor protein.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7971926

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Apolipoprotein E.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7249055

-

ZenodoAntibody characterization report for Calpain-2 catalytic subunit.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5259215

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Charged multivesicular body protein 2b.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6370501

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Coiled-coil-helix-coiled-coil-helix domain-containing protein 10, mitochondrial (CHCHD10).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5259992

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Itchy homolog (Itch).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6566970

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase parkin (Parkin).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5747356

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Endothelin-converting enzyme 1.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7459248

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 SLC29A1 (ENT1).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7324605

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7987195

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6941512

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Mitogenactivated protein kinase 1 (MAPK1).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6941499

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 2 (NDUFS2).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5903708

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Neurosecretory protein VGF.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5903141

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for QPRTase (Nicotinate-nucleotide pyrophosphorylase [carboxylating]).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7459387

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for RNA-binding protein TIA1.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7671718

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Plasma membrane calcium-transporting ATPase 1.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7971932

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Prolow-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein1 (LRP-1).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7971951

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Retinoic acid receptor RXR-alpha.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6566983

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 (Rho GDI 1).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7249221

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for RNA-binding protein FUS.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5259945

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Secreted frizzled-related protein 1.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6370454

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Serine protease HTRA1.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7986850

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Serine/threonine-protein kinase Nek1.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5061736

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Serine/threonine-protein kinase TBK1.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6402968

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Sigma non-opioid intracellular receptor 1.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5644356

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5B (STAT5B).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7249185

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for SPARC-related modular calcium-binding protein 1 (SMOC1).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6566878

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] (SOD1).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5061103

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Valosin-containing protein VCP.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7971904

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Transmembrane protein 106B.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7459629

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Tubulin alpha-4A chain.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7987237

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for TYRO protein tyrosine kinase-binding protein (TYROBP).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6941517

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Tyrosine-protein kinase SYK.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6566940

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for hVPS35 (Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 35).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7671730

-

ZenodoAntibody Characterization Report for Vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B/C (VAPB).https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6370535

References

-

The Antibody Registry: ten years of registering antibodiesNucleic Acids Research 51:D358–D367.https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac927

-

Target 2035: probing the human proteomeDrug Discovery Today 24:2111–2115.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2019.06.020

-

Animal-friendly affinity reagents: replacing the needless in the haystackTrends in Biotechnology 34:960–969.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.05.017

-

Animal-free alternatives and the antibody icebergNature Biotechnology 38:1234–1239.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0687-9

-

SHANK3 Antibody validation: Differential performance in western blotting, immunocyto- and immunohistochemistryFrontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience 14:890231.https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2022.890231

-

Change-makers bring on recombinant antibodiesNature Methods 17:763–766.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-0915-8

-

Antibody validation for Western blot: By the user, for the userThe Journal of Biological Chemistry 295:926–939.https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.RA119.010472

-

Ten approaches that improve immunostaining: A review of the latest advances for the optimization of immunofluorescenceInternational Journal of Molecular Sciences 23:1426.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23031426

-

A proposal for validation of antibodiesNature Methods 13:823–827.https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3995

Peer review

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The research addresses a key problem in life sciences: While there are millions of commercially available antibodies to human proteins, researchers often find that the reagents do not perform in the assays they are specified for. The consequence is wasted time and research funding, and the publication of misleading results.

Manufacturers' catalogues often contain images of western blots. Researchers are likely to select antibodies that stain a single band at the position expected from the mass of the intended target. However, the good results shown in catalogues are often not reproduced when researchers use the antibody in their own laboratories. A single band is also weak evidence since many proteins have similar mass and because assessment of mass by WB is at best approximate. In addition, results obtained by WB may not predict performance in applications where the antibody is used to recognize folded proteins. Examples include immunoprecipitation (IP) of native proteins in cell lysates and staining of viable or formalin-fixed/permeablized cells for flow cytometry or immunofluorescence microscopy (IF).

The authors of this manuscript are from the Canadian, public interest open-science company YCharos. The company webpage (ycharos.com) explains that they have partnered with many leading manufacturers of research antibodies and that their mission is to characterize commercially available antibody reagents for every human protein.

The authors have developed a standardized pipeline where antibodies are used in WB, IP of native proteins from cell lysates (WB readout) and IF (staining of cell lines that have been fixed with paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Triton x100). A key component is the use of knockout cell lines as negative controls in WB and IF. Eight cell lines were selected as positive controls on the basis of mRNA expression data that are publicly available in the Expression 22Q1 database.

Reports for antibodies to each protein are made available online at https://ZENODO.org/communities/ycharos/ as images of western blots, and immunofluorescence staining. In addition, reports for each target are available at https://ycharos.com/data/ .

MANUSCRIPT:

The manuscript describes validation criteria and results obtained with 614 commercially available antibodies to 65 proteins relevant for neuroscience A major achievement is the identification of successful renewable antibodies for 50/56 (77%) proteins in WB, 49/65 (75%) for IP and (54%) for IF. There can be little doubt that the approach represents a gold standard in antibody validation. The manuscript therefore represents a guide to a very valuable resource that should be of considerable interest to the scientific community.

While the results are convincing, they could be more accessible. In the current format, researchers have to download reports for each target and look through all images to identify the most useful antibodies from the images. The reports I reviewed did not draw conclusions on performance. A searchable database that returns validated antibodies for each application seems necessary.

It is worth noting that 95% of the tested antibodies were specified by the manufacturer for use in WB. This supports the view that manufacturers use WB as a first-pass test (Nat Methods. 2017 Feb 28;14(3):215) and that most commercial antibodies are developed to recognize epitopes that are exposed in unfolded proteins. Important exceptions are those used for ELISA or staining of viable cells for flow cytometry. 44% of antibodies specified for WB were classified as "successful" meaning a single band that was absent in the negative control (knockout/KO lysate). Another 35% detected the intended target but showed additional bands that were present also in the KO lysate. A key question is to what extent off-target binding was predictable from the WBs provided by the manufacturers. Thus, how often did the authors find multiple bands when the catalogue image showed a single band and vice versa?

The authors correctly point out that manufacturers rarely test their reagents in IP. Thus, there is little information about antibodies capable of binding folded proteins. It is encouraging that as many as 37% of those not specified for IP were able to enrich their targets from cell lysates. Yet it is important to explain that a test that involves readout by WB provides information about on-target binding only. Cross-reactive proteins will generally not be detected when blots are stained with an antibody reactive with a different epitope than the one used for IP. Possible solutions to overcome this limitation such as the use of mass spectrometry as readout should be discussed (Nature Methods volume 12, pages 725-731 2015).

Performance in immunofluorescence microscopy was performed on cells that were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X100. It seems reasonable to assume that this treatment mainly yields folded proteins wherein some epitopes are masked due to cross-linking. The expectation is therefore that results from IP are more predictive for on-target binding in IF than are WB results (Nature Methods volume 12, pages725-731 2015). It is therefore surprising that IP and WB were found to have similar predictive value for performance in IF (supplemental Fig. 3). It would be useful to know if failure in IF was defined as lack of signal, lack of specificity (i.e. off-target binding) or both. Again, it is important to note the IP/western protocol used here does not test for specificity.

The authors report that recombinant antibodies perform better than standard monoclonals/mAbs or polyclonal antibodies. Again, a key question is to what extent this was predictable from the validation data provided by the manufacturers. It seems possible that the recombinant antibodies submitted by the manufacturers had undergone more extensive validation than standard mAbs and polyclonals.

Overall, the manuscript describes a landmark effort for systematic validation of research antibodies. The results are of great importance for the very large number of researchers who use antibodies in their research. The main limitations are the high cost and low throughput. While thorough testing of 614 antibodies is impressive and important, the feasibility of testing hundreds of thousands of antibodies on the market should be discussed in more detail.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.91645.2.sa1Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The paper nicely demonstrates the extent of the issue with the unreliability of commercial antibodies and describes a highly significant initiative for the robust validation of antibodies and recording this data so that others can benefit. It is a great idea to have all individual antibody characterisation reports available on Zenodo - these reports are comprehensive, clear and available to everyone.

A significant proportion of all life science research conclusions are based on data obtained through the use of antibodies. The quality and specificity of antibodies vary significantly. Until now there has been no uniform generally recognised approach to how to systematically assess and rate antibody specificity and quality. Furthermore, the applications that a particular antibody can be used in including western blot, immunofluorescence or immunoprecipitation are frequently not known. This paper provides important guidelines for how the quality of an antibody should be assessed and recorded and data made freely available via a Zenodo repository. This study will ensure that researchers only use well-validated antibodies for their work. A worrying aspect of this paper is that many poor-quality antibodies that failed validation are reportedly being widely used in the literature. More than 60% of all antibodies recommended for immunofluorescence failed QC. This study will have broad interest. I would recommend that all researchers select their antibodies using the database described in the paper and follow its recommendations for how antibodies should be thoroughly validated before being used in research. Hopefully, other researchers can contribute to this database in the future all widely used antibodies will eventually be well characterized. This should improve the quality and reproducibility of life science research.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.91645.2.sa2Author response

Reviewer #1:

We thank Reviewer #1 for their review of our manuscript.

Reviewer #1, comment #1: “The authors of this manuscript are from the Canadian, public interest open-science company YCharos.”.

It is important to state that none of the authors work for YCharOS. The YCharOS company has created an open ecosystem consisting of antibody manufacturers, knockout cell lines providers, academics, granting agencies and publishers. The Antibody Characterization Group (participating authors are affiliated to the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Structural Genomics Consortium, The Montreal Neurological Institute, McGill University) works in collaboration with YCharOS to have access to commercial antibodies and knockout cell lines donated by YCharOS’ manufacturer partners.

Reviewer #1, comment #2: In regard to ZENODO antibody characterization reports prepared by this group, Reviewer #1 wrote: “While the results are convincing, they could be more accessible. In the current format, researchers have to download reports for each target and look through all images to identify the most useful antibodies from the images. The reports I reviewed did not draw conclusions on performance. A searchable database that returns validated antibodies for each application seems necessary.”

After careful consideration and consultation with YCharOS industry partners, we decided not to rate the performance of the antibodies tested. It was determined that antibody selection is best left to the user, who should analyze all parameters, including the type of antibody to be chosen (recombinant-monoclonal, recombinant-polyclonal, monoclonal), the species used to generate the antibody, the species predicted to react with the antibody, performance in a specific application, antigen sequences, and antibody cost.

Reviewer #1, comment #3: “A key question is to what extent off-target binding was predictable from the WBs provided by the manufacturers. Thus, how often did the authors find multiple bands when the catalogue image showed a single band and vice versa?”

In many cases, the antibodies were tested on cell lines other than those used by the manufacturers. Given that protein expression is specific to each line, we can't answer this question properly.

Reviewer #1, comment #4: “Cross-reactive proteins will generally not be detected when blots are stained with an antibody reactive with a different epitope than the one used for IP. Possible solutions to overcome this limitation such as the use of mass spectrometry as readout should be discussed (Nature Methods volume 12, pages 725- 731 2015)”.

Our protocols only inform whether an antibody can capture the intended target, without any evaluation of the extend to the capture of unwanted, cross-reactive proteins. Thus, our data can only be used to aid in selection of the best performing antibodies for IP – our data does not inform profiling of non-specific interactions.

IP/mass spec is an excellent approach for evaluating antibody performance for IP, and authors on this manuscript are experts in proteomics and recognize the importance of this methodology. We have considered implementing IP/mass in our platform. However, there are limitations, such as the cost of the approach and the difficulty of detecting smaller proteins or proteins with a certain amino acid composition (high presence of Cys, Arg or Lys). Fundamentally, we have decided to focus on throughput relative to details in this regard.

Reviewer #1, comment #5: “Performance in immunofluorescence microscopy was performed on cells that were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X100. It seems reasonable to assume that this treatment mainly yields folded proteins wherein some epitopes are masked due to cross-linking. The expectation is therefore that results from IP are more predictive for on-target binding in IF than are WB results (Nature Methods volume 12, pages725-731 2015). It is therefore surprising that IP and WB were found to have similar predictive value for performance in IF (supplemental Fig. 3). It would be useful to know if failure in IF was defined as lack of signal, lack of specificity (i.e. off-target binding) or both. Again, it is important to note the IP/western protocol used here does not test for specificity.”

The assessment of antibody performance is biased by how antibodies were originally tested by suppliers. Manufacturers primarily validate their antibody by WB. Thus, most antibodies immunodetect their intended target for WB. Thus, in retrospect, we tested a biased pool of antibodies that detect linear epitopes. Still, we observed that a large cohort of antibodies show specificity for their target across all three applications or for specific combinations of applications. This slightly challenges the idea that antibodies are fit-for-purpose reagents and can recognize either linear or native epitopes - a significant number of antibodies can specifically detect both types of epitope.

Reviewer #1, comment #6: “The authors report that recombinant antibodies perform better than standard monoclonals/mAbs or polyclonal antibodies. Again, a key question is to what extent this was predictable from the validation data provided by the manufacturers. It seems possible that the recombinant antibodies submitted by the manufacturers had undergone more extensive validation than standard mAbs and polyclonals”.

Our antibody manufacturing partners indicated that the recombinant antibodies are more recent products and have been more extensively characterized relative to standard polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies.

The main message is that recombinant antibodies can be used in all applications once validated. Although recombinant antibodies are available for many proteins, the scientific community is not adopting these renewable regents as we believe it should. We hope that the data provided will encourage scientists to adopt recombinant technologies when available to improve research reproducibility.

Reviewer #1, comment #7: “Overall, the manuscript describes a landmark effort for systematic validation of research antibodies. The results are of great importance for the very large number of researchers who use antibodies in their research. The main limitations are the high cost and low throughput. While thorough testing of 614 antibodies is impressive and important, the feasibility of testing hundreds of thousands of antibodies on the market should be discussed in more detail.”

We thank the reviewer for this comment. One of our challenges is to increase the platform's throughput to succeed in our mission to characterize antibodies for all human gene products. We will continue to test antibodies using protocols agreed upon with our partners, commonly used in the laboratory, to ensure that ZENODO reports can serve as a guide to the wider community.

In terms of development our marketing efforts have been substantially accelerated by our new partnership with the journal F1000. We have begun to convert our reports into peer-reviewed papers (20 ZENODO reports were converted into F1000 articles). This conversion allows researchers to find our work via PubMed, and easily cite any study. Producing peer-reviewed articles also further enhances the credibility of our research and our project as a whole: https://f1000research.com/ycharos

Colleagues have published a letter to Nature explaining the problem and our technology platform: (Kahn, et al., Nature, 2023, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02566-w).

This project has been presented worldwide, with a presence at major antibody conferences, such as the annual Antibody Validation meeting in Bath (PSM attended the meeting in September 2023). The authors are organizing a sponsored mini-symposium on antibody validation at the next American Society for Cell Biology (ASCB) meeting in December 2023 (Boston, USA): https://plan.core- apps.com/ascbembo2023/event/6fb928f06b0d672e088c6fa88e4d77fb

Colleagues have prepared petitions addressed to various governmental organizations (US, Canada, UK) to support characterization and validation of renewable antibodies: https://www.thesgc.org/news/support- characterization-and-validation-renewable-antibodies.

Reviewer #2

We thank Reviewer #2 for the review of the antibody characterization reports we have uploaded to ZENODO. A manuscript describing the full standard operating procedures of the platform, which has been used in all reports is in preparation, and should be available on a preprint server before the end of the year. Our protocols were reviewed and approved by each of YCharOS' manufacturer partners. Moreover, a recent editorial describes the platform used here and gives advice on how to interpret the data: https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.141719.1

Reviewer #2, comment #1: “A discussion of how the working concentrations of antibodies are selected and validated is required. Based on the dilutions described in the reports, it seems that dilutions suggested by the manufacturer were used - For LRRK2 it seems that antibody concentrations ranging from 0.06 to over 5 µg/ml for WB were used. Often commercial antibody comes in a BSA-containing buffer making it hard to validate the concentration of the antibody claimed by the manufacturer”.

The concentration recommended by the manufacturer is our starting point. For WB, when the signal is at the level of detectability, we will repeat with a ~5-10 fold increase in antibody concentration. For >80% of the antibody tested, the use of the recommended concentration led to the detection of bands (specific or not to the target protein).

Reviewer #2, comment #2: “In the authors' experience are the manufacturer's concentrations reliable? Additionally, if the information regarding applications provided by the manufacturers is unreliable how do the authors suggest working concentrations for antibodies to be assessed”?

We do not evaluate the concentration of antibodies internally. In the immunoprecipitation experiments, we use 2.0 µg of antibody for each IP, based on the concentration provided by the manufacturers. On Ponceau staining of membranes, we can observe the heavy and light chains of the primary antibodies used, giving an indication of the amount of antibodies added to the cell lysate. In most cases, the intensity of the heavy and light chains is comparable.

Reviewer #2, comment #3: “We understand that it would not be feasible to test every antibody at different concentrations, but this is an issue that should at least be mentioned. An antibody might be put in the wrong performance category solely because of the wrong concentration being used. Ie if an excellent antibody is used at too high a concentration, it may detect non-specific proteins that are not seen at lower dilutions where the antibody still picks up the desired antigen well”.

We agree with Reviewer #2, we do not use an optimal concentration for all tested antibodies. As mentioned previously, the concentration recommended by the manufacturer is our starting point. By testing multiple antibodies side-by-side against a single target protein, we can generally identify one or more specific and selective antibodies. We leave it to users of our reports to optimize the antibody concentration to suit their experimental needs.

Reviewer #2, comment #4: “Do the authors check different WB conditions ie 2h primary antibody with BSA or milk vs. overnight at 4 degrees with BSA or Milk”?

All primary antibodies are always tested in milk overnight at 4 degrees. The overnight incubation is convenient in the timeline of the protocol. All protocols were agreed upon after careful consultation with our partners.

Reviewer #2, comment #5: “Do the authors provide detailed WB protocols that include the description of the electrophoresis and type of gels used, transfer buffer and transfer method and time used, and conditions for all the primary and secondary blotting including times, buffers and dilutions of all antibodies and other reagents”?

This information is included in all ZENODO reports.

Reviewer #2, comment #6: “Do the authors discuss detection approaches- we have noticed for some antibodies there are significant different results using LICOR, ECL and other detection methods, with certain especially weaker antibodies preferring ECL-based methods”.

We only use ECL-based methods.

Reviewer #2, comment #7: “For IPs the amount of antibody needed can also vary-for some we can use 1 microgram or less, but for others, we need 5 to 10 micrograms. The amount of antibody needed to get maximal IP should be stated”.

We use 2.0 ug of antibodies and we have found this to be adequate for lower abundance proteins (e.g. Parkin - https://zenodo.org/records/5747356) and higher abundance proteins (e.g. PRDX6 - https://zenodo.org/records/4730953). Abundance is based on PaxDb.com. For Parkin and PRDX6, we were able to enrich the expected target in the IP and observe depletion in the unbound fraction. Optimization of the IP conditions is left to the antibody users.

Reviewer #2, comment #8: “Doing IPs with commercial antibodies can be very expensive or infeasible if many micrograms are needed especially if only packages of 10 micrograms for several hundred dollars are provided”.

This is a major advantage of the side-by-side comparison: the reader is free to choose between high-performance antibodies from different manufacturers, with varying antibody costs. We also work in partnership with the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Band (DSHB), which supplies antibodies on a cost recovery basis.

Reviewer #2, comment #9: “For IPs it is important to determine the percentage of antigen that is depleted from the supernatant for each IP. We think that this should be calculated and recorded in the Zenodo data. Some antibodies will only IP 10% of antigen whereas others may do 50% and others 80-90%. One rarely sees 100% depletion. For IPs the buffer detergent and salt concentration might also strongly influence the degree of IP and therefore these should be clearly stated”.

In Box 1, we define criteria of success. For IP, “under the conditions used, a successful primary antibody immunocaptures the target protein to at least 10% of the starting material”. Colleagues have written an editorial on how to interpret and analyze antibody performance https://f1000research.com/articles/12-1344.

The cell lysis buffer is a critical reagent when considering IP experiments. We use a commercial buffer consisting of 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40 and 5% glycerol (Thermo Fisher, cat. #87787). This buffer is efficient to extract the target proteins we have studied thus far.

Reviewer #2, comment #10: “Whether antibodies cross-react with human, mouse and other species of antigens is always a major question. It is always good to test human and mouse cell lines if possible. If antibodies cross-react in WB, in the authors' experience will they also cross-react for IF and IP”?

The authors started this initiative by focusing on the 20,000 human proteins, defining an end point. We and our collaborators found that most of the cherry-picked selective antibodies for WB for human proteins, which manufacturers claim react with the murine version of the target proteins, were selective for murine tissue lysates.

Indeed, poorly performing antibodies in WB mostly failed IF and IP. However, selective antibodies for IF or specific for IP were generally (>90%) selective for WB.

Reviewer #2, comment #11: “Cell lines express proteins at vastly different levels and it is possible that the selected cell line does not express the antigen or expresses it at very low levels - this could be a reason for wrongly assessing an antibody not working. It would be useful to use cell lines in which MS data has defined the copy number of protein per cell and this figure could be included in the antibody data if available. This MS data is available for the vast majority of commonly used cells”.

We agree with Reviewer #2 that MS data are useful for target protein selection. At the moment, our approach using transcriptomic data provided on DepMap.org proved to be a successful mechanism for cell line selection. We have identified a specific antibody for WB for each target, enabling the validation of expression in the cell line selected.

For some protein targets, the parental line corresponding to the only commercial or academic knockout line available has weak protein expression. We thus needed to generate a KO clone in a second cell line background with high expression, and indeed found that some antibodies which failed in the first commercial line were successful in the new higher-expressing line (e.g CHCHD10 - https://zenodo.org/records/5259992).

Reviewer #2, comment #12: “Some proteins are glycosylated, ubiquitylated or degraded rapidly making them hard to see in WB analysis”.

We used the full gel/membrane length when analyzing antibody performance by WB. Indeed, proteins can show different isoforms and molecular weights compared to that based on amino acid sequence (e.g. SLC19A1 -https://zenodo.org/records/7324605).

Reviewer #2, comment # 13: “We have occasionally had proteins that appear unstable when heated with SDS- sample buffer before WB. For these, we still use SDS-Sample buffer but omit the heating step. I often wonder how necessary the heating step is”.

For WB, samples are heated to 65 degrees, then spun to remove any precipitate.

Reviewer #2, comment # 14: “For IF the methods by which cells are fixed and stained, and the microscope and settings, can significantly influence the final result. It would be important to carefully record all the methods and the microscope used”.

We agree with Reviewer #2 that many parameters influence antibody performance for imaging purposes. We are progressively implementing the OMERO software to monitor any experimental parameters and information (metadata) about the microscope itself.

Reviewer #2, comment # 15: “How do the authors recommend antibodies are stored? These should be very stable, but I have had reports from the lab that some antibodies become less good when stored and others that recommend storing at 4 degrees”.

Antibodies are aliquoted to avoid freeze-thaw cycles and stored at -20 degrees. If it is recommended to store antibodies at 4 degrees, we add glycerol to a final concentration of 50% and store them at -20 degrees.

Reviewer #2, comment # 16: “Would other researchers not part of the authors' team, be able to add their own data to this database validating or de-validating antibodies? This would rapidly increase the number of antibodies for which useful data would be available for. It would be nice to greatly expand the number of antibodies being used in research and this is not feasible for a single team to undertake”.

Yes! We believe that only a community effort can resolve the antibody liability crisis. We partner with the Antibody Registry (antibodyregistry.org - led by co-author Anita Bandrowski). In the Registry, each antibody is labelled with a unique identifier, and third-party validation information can be easily tagged to any antibody. Antibody users are invited to upload information about an antibody they have characterized into the Registry.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.91645.2.sa3Article and author information

Author details

Funding

National Institute on Aging (U54AG065187)

- Aled M Edwards

Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research (18331)

- Peter McPherson

ALS Society of Canada

- Thomas M Durcan

- Aled M Edwards

- Peter McPherson

- Carl Laflamme

ALS Association

- Thomas M Durcan

- Aled M Edwards

- Peter McPherson

- Carl Laflamme

Motor Neurone Disease Association

- Thomas M Durcan

- Aled M Edwards

- Peter McPherson

- Carl Laflamme

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN154305)

- Peter McPherson

Genome Canada (OGI-210)

- Peter McPherson

- Carl Laflamme

Genome Quebec (OGI-210)

- Peter McPherson

- Carl Laflamme

Mitacs (Postdoctoral Fellowship)

- Riham Ayoubi

National Institute on Aging (RF1AG057443)

- Aled M Edwards

Ontario Genomics (OGI-210)

- Peter McPherson

- Carl Laflamme

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements