Multiple cullin-associated E3 ligases regulate cyclin D1 protein stability

Abstract

Cyclin D1 is a key regulator of cell cycle progression, which forms a complex with CDK4/6 to regulate G1/S transition during cell cycle progression. Cyclin D1 has been recognized as an oncogene since it was upregulated in several different types of cancers. It is known that the post-translational regulation of cyclin D1 is controlled by ubiquitination/proteasome degradation system in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Several cullin-associated F-box E3 ligases have been shown to regulate cyclin D1 degradation; however, it is not known if additional cullin-associated E3 ligases participate in the regulation of cyclin D1 protein stability. In this study, we have screened an siRNA library containing siRNAs specific for 154 ligase subunits, including F-box, SOCS, BTB-containing proteins, and DDB proteins. We found that multiple cullin-associated E3 ligases regulate cyclin D1 activity, including Keap1, DDB2, and WSB2. We found that these E3 ligases interact with cyclin D1, regulate cyclin D1 ubiquitination and proteasome degradation in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. These E3 ligases also control cell cycle progression and cell proliferation through regulation of cyclin D1 protein stability. Our study provides novel insights into the regulatory mechanisms of cyclin D1 protein stability and function.

Editor's evaluation

This fundamental study advances our understanding of the role of cullin-associated E3 ligases in regulating cyclin D1 protein stability. The evidence supporting the conclusion is compelling, from siRNA screens and ectopic expression approaches. This paper is of potential interest for cell biologists studying the mechanisms of protein posttranslational modification.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.80327.sa0Introduction

Cyclin D1 is a key factor controlling cell cycle progression. It forms a complex with CDK4/6 and functions as a regulatory subunit in G1/S phase transition during cell cycle progression. Proteasome degradation is one of the critical post-translational regulatory mechanisms modulating steady-state protein levels of cyclin D1 during normal cell cycle progression (Qie and Diehl, 2020). Cullin-Ring complexes comprise the largest known family of ubiquitin ligases. Human cells express seven different cullins, CUL1, -2, -3, -4A, -4B, -5, and -7, and each of them nucleates a different ubiquitin ligase (Petroski and Deshaies, 2005). Recent studies demonstrate that F-box proteins Fbxw8, Fbx4, Fbxo31, and AMBRA1 interact with CUL1/7 and mediate cyclin D1 degradation in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (Chaikovsky et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2005; Li et al., 2018; Maiani et al., 2021; Okabe et al., 2006; Santra et al., 2009; Simoneschi et al., 2021). However, it is not known if other E3 ligase(s) is also involved in maintaining steady-state protein levels of cyclin D1. In this study, we have screened an E3 ligase siRNA library and identified three additional cullin-associated E3 ligases, which mediate cyclin D1 ubiquitination and proteasome degradation. Our findings indicate multiple cullin-associated E3 ligases participate in the regulation of cyclin D1 stability in the cells.

Results and discussion

To determine if cullins are required for cyclin D1 degradation, CUL1–7 (CUL1, -2, -3, -4A, -4B, -5, and -7) expression plasmids were co-transfected with cyclin D1 into HEK293 cells. Forced expression of CUL1–7 significantly suppressed cyclin D1 protein levels (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A). In contrast, the levels of cyclin B1 (G2/M regulator) and cyclin A (S phase regulator) were not affected (Figure 1—figure supplement 1A), indicating that the CUL1–7 specifically regulate cyclin D1 protein levels. Consistent with these findings, RNAi-mediated knockdown of cullins significantly enhanced levels of endogenous cyclin D1 (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B). The knockdown efficiency of these siRNAs to each cullin mRNA was about 60–90% (Figure 1—figure supplement 2). In addition, the silencing specificity of each cullin siRNA has been verified through both western blotting and real-time PCR assays (Figure 1—figure supplements 3 and 4). Results of luciferase assay also showed that cullins inhibited cyclin D1 activity (Figure 1—figure supplement 5). In contrast, silencing of the cullins led to increased cyclin D1 activity (Figure 1—figure supplement 6).

We then determined whether cullin-induced cyclin D1 degradation is ubiquitin-dependent and performed ubiquitination assay. We found that forced expression of CUL1–7 resulted in polyubiquitination of wild-type (WT) cyclin D1 (Figure 1—figure supplement 7). It was noted that CUL4B and CUL7 exhibited the most significant effect on cyclin D1 ubiquitination compared with other cullins. In contrast, CUL1–7 had no effects on the ubiquitination of mutant cyclin D1 with phosphorylation defect (T286A) (Figure 1—figure supplement 7). It has been reported that Thr286 phosphorylation is required for cyclin D1 ubiquitination (Diehl et al., 1997). Our results suggest that cullin-induced cyclin D1 ubiquitination is phosphorylation-dependent. A proteasome degradation inhibitor, MG132, was used to further determine if the cullins-mediated cyclin D1 degradation is through a proteasome-dependent mechanism. MG132 significantly reversed cyclin D1 degradation induced by CUL1–7 (Figure 1—figure supplement 8). Compared with their effects on cyclin D1 protein degradation, CUL1–7 had no significant effects on cyclin D1 mRNA expression (Figure 1—figure supplement 9). These results demonstrated that these seven human cullins may play critical and redundant roles in cyclin D1 degradation through a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism.

Each cullin protein interacts with different multi-subunit ubiquitin ligases (Petroski and Deshaies, 2005). Hundreds of substrate receptor subunits associated with different cullin-Ring ligases have been characterized in mammalian cells (Petroski and Deshaies, 2005). To identify additional E3 ligases which are associated with cullin proteins and are involved in cyclin D1 degradation, we generated an siRNA library targeting known cullin-associated proteins. This library contains triplicated siRNAs targeting to specific genes encoding for 154 ligase subunits, including F-box, SOCS, BTB-containing proteins, and DDB proteins. We transfected these siRNAs with 3xE2F-Luc reporter construct into NIH3T3 cells. 3xE2F-Luc reporter specifically responds to cyclin D1 stimulation (Ohtani et al., 1995). After screening the siRNA library, we found that 3xE2F luciferase activity was enhanced by 24 E3 ligases (>1.5-fold increase) (Figure 1—figure supplement 10). These results suggest that multiple E3 ligases associated with different cullin proteins are involved in cyclin D1 degradation. We selected five E3 ligases, which showed highest stimulation activities on the 3xE2F-Luc reporter and found that all of them have the ability to reduce cyclin D1 protein levels in HEK293 cells (Figure 1—figure supplement 11). Among these E3 ligase subunits, Fbxw8 (specific for CUL1 and -7) has been reported to induce cyclin D1 degradation (Okabe et al., 2006). The roles of other E3 ligase subunits, such as Keap1 (associated with CUL3), DDB2 (associated with CUL4A and -4B), and WSB2 (associated with CUL2 and -5) in cyclin D1 degradation have not been reported.

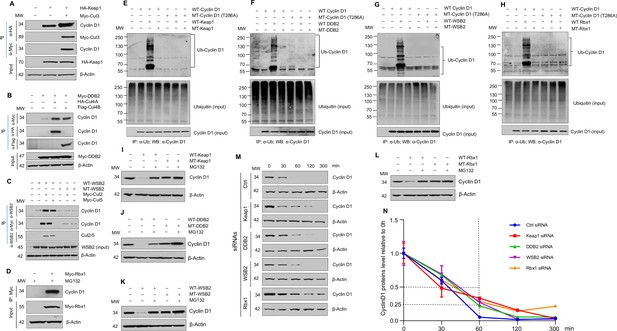

To further test the hypothesis that cyclin D1 degradation is mediated by multiple E3 ligases, we determined if different E3 ligases, Keap1, DDB2, and WSB2, are involved in cyclin D1 proteolysis. We first examined the interaction of these E3 ligases with cyclin D1 through co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with HA-tagged Keap1 and treated with MG132 to prevent cyclin D1 degradation. Endogenous cyclin D1 was detected in the Keap1 immunoprecipitate, and this interaction was enhanced by the CUL3 (Figure 1A). Similarly, the interaction of DDB2 with endogenous cyclin D1 was enhanced by the CUL4A and -4B (Figure 1B). Consistent with these results, we also observed that CUL2 and -5 enhanced the interaction between WSB2 and endogenous cyclin D1 (Figure 1C). Rbx1 is associated with CUL1–7 and was used as a control in this study. The results of co-IP assay showed that Rbx1 interacted with endogenous cyclin D1 (Figure 1D).

Cullin-associated E3 ligases mediate cyclin D1 ubiquitination and proteasome degradation.

(A) Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of Keap1, CUL3 with endogenous cyclin D1. HA-Keap1 and Myc-CUL3 were co-transfected into HEK293 cells with the MG132 treatment (10 μM, 4 hr incubation). 24 hr after transfection, the cell lysates were collected. To detect interaction of Keap1 with cyclin D1 or CUL3, co-IP was performed using the anti-HA (α-HA) antibody followed by the western blot using the anti-cyclin D1 or anti-Myc (α-Myc) antibody. To detect the interaction between CUL3 with cyclin D1, co-IP assay was performed using the anti-Myc antibody followed by the western blot using the anti-cyclin D1 antibody. (B) Co-IP of DDB2 and CUL4A/4B with endogenous cyclin D1. Myc-DDB2, HA-CUL4A, and Flag-CUL4B were transfected into HEK293 cells with the MG132 treatment (10 μM, 4 hr incubation). Co-IP was performed using the anti-Flag (α-Flag), anti-HA, or anti-Myc antibody followed by the western blot using the anti-cyclin D1 antibody. (C) Co-IP of WSB2 and CUL2/5 with endogenous cyclin D1. Wild-type (WT) or mutant form of WSB2 (SOCS∆364–400) were co-transfected with Myc-CUL2/5 into HEK293 cells with MG132 treatment (10 μM, 4 hr incubation). Co-IP was performed using the anti-Myc or anti-WSB2 (α-WSB2) antibodies followed by the western blot using the anti-cyclin D1 antibody. (D) Co-IP of Rbx1 with endogenous cyclin D1. Myc-Rbx1 was transfected into HEK293 cells with MG132 treatment (10 μM, 4 hr incubation). Co-IP assay was performed using the anti-WSB2 or anti-Myc antibody followed by the western blot using the anti-cyclin D1 antibody. (E–H) Ubiquitination assay. WT or mutant cyclin D1 (T286A) were co-transfected with WT or mutant Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 expression plasmids into HEK293 cells with the treatment of MG132 (10 μM, 4 hr incubation). Co-IP was performed using the anti-Ub (α-Ub) antibody followed by the western blot using the anti-cyclin D1 (α-cyclin D1) antibody. (I–L) WT or mutant Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, and Rbx1 expression plasmids were co-transfected with cyclin D1 expression plasmid into HEK293 cells with the MG132 treatment (10 μM, 4 hr incubation). Cyclin D1 protein levels were detected by the western blot analysis. (M, N) Protein decay assay. HEK293 cells were transfected with scramble siRNA (Ctrl) or Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 siRNA. The cell lysates were collected 0, 30, 60, 120, or 300 min after cycloheximide treatment (80 μg/ml) and the cyclin D1 protein levels were detected by the western blot analysis and were quantified (n=3).

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Numerical data obtained during experiments represented in Figure 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/80327/elife-80327-fig1-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 1—source data 2

Original western blot files for Figure 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/80327/elife-80327-fig1-data2-v2.zip

We then examined the effects of Keap1, DDB2, and WSB2 on cyclin D1 ubiquitination and degradation and used loss-of-function mutants of these E3 ligases to do experiments. In addition, we used Rbx1 as a control in these experiments. For Keap1, we used BTB domain deletion form which abolishes its binding with CUL3 (Furukawa and Xiong, 2005). For DDB2, we used the WD motif deletion form which blocks its binding to its substrates (Nag et al., 2001). For WSB2, we used the C-terminal deleted mutant which loses its binding to CUL2 and -5. And for Rbx1, we used the mutant form Rbx1C53A/C56A which dramatically reduced the ligase activity (Ohta et al., 1999). We found that WT but not mutant Keap1 (F-box mutation) induced cyclin D1 ubiquitination (Figure 1E). In contrast, Keap1 had no effect on the ubiquitination of phosphorylation mutant cyclin D1 (T286A) (Figure 1E). Similarly, WT DDB2, WSB2, and Rbx1 induced cyclin D1 ubiquitination and mutant DDB2, WSB2, and Rbx1 had no effects on cyclin D1 ubiquitination (Figure 1F–H). In addition, Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 had no effects on the ubiquitination of phosphorylation mutant cyclin D1 (T286A) (Figure 1E–H). These results indicate that Keap1, DDB2, and WSB2 interact with cyclin D1 and mediate cyclin D1 ubiquitination in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. We then determined the effects of these E3 ligases on cyclin D1 degradation by western blot analysis. Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, and Rbx1 induced WT but not T286A mutant cyclin D1 degradation (Figure 1I–L). In contrast, mutant Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 had no effect on cyclin D1 degradation (Figure 1I–L). Consistent with these findings, silencing of Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 resulted in the stabilization of cyclin D1 protein and significantly prolonged the half-life of cyclin D1 (Figure 1M and N). The silencing specificity of siRNA for each E3 ligase subunit has been verified through real-time PCR assays (Figure 1—figure supplement 12). To determine the effects of these E3 ligases on protein levels of endogenous cyclin D1, we transfected Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, and Rbx1 siRNA into human colon cancer cell line HCT-116 cells and found that knocking down of Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 significantly enhanced endogenous cyclin D1 protein levels (Figure 2A, D, G, and J). Taken together, these findings indicate that cyclin D1 degradation is mediated by multiple E3 ligases which are associated with different cullin proteins.

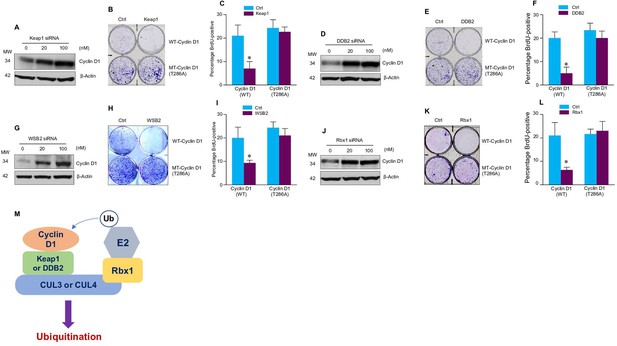

Cullin-associated E3 ligases affect cyclin D1 function.

(A, D, G, J) Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 siRNAs were transiently transfected into human colon cancer cell line HCT-116 cells. Endogenous cyclin D1 protein levels were detected by the western blot using the anti-cyclin D1 antibody. (B, E, H, K) Cell proliferation assay. Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 expression plasmids were transfected into HCT-116 cells which were stably transfected with wild-type (WT) or mutant cyclin D1 (T286). The cells were stained with crystal violet 5 days after Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 transfection. (C, F, I, L) Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay. Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 expression plasmid was transiently transfected into HCT-116 cells which were stably transfected with WT or mutant cyclin D1 (T286). 4 hr before the harvest of cells, the cells were treated with BrdU (20 μM). 48 hr after the transfection, BrdU incorporation assays were performed (n=3). Data were presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA followed by the Tucky’s post-hoc test, *P<0.05 (n=3). (M) A model showing that cullin-associated ubiquitin ligases are participated in the cyclin D1 proteolysis process.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Numerical data obtained during experiments represented in Figure 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/80327/elife-80327-fig2-data1-v2.xlsx

-

Figure 2—source data 2

Original western blot files for Figure 2.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/80327/elife-80327-fig2-data2-v2.zip

We then determined whether these E3 ligases affect the function of cyclin D1 during normal cell cycle progression. Over-expression of Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 markedly inhibited the growth of HCT-116 cells. In contrast, these E3 ligases had no effect on cell proliferation in the cells stably transfected with T286A mutant cyclin D1 (Figure 2B, E, H, and K). Then, we performed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis and treated cells with nocodazole to synchronize the cell division cycle. We found that in HCT-116 cells stably transfected with the WT cyclin D1, forced expression of Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 prevented the nocodazole-mediated G2/M block and subsequently resulted in accumulation of cells in G1 phase (Figure 2—figure supplement 1). In contrast, Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 failed to induce efficient cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase in the mutant cyclin D1 (T286A) transfected cells (Figure 2B, E, H, and K). The results indicate that these cullin-associated ubiquitin ligases promoted cyclin D1 degradation and subsequently decreased cell cycle progression rate in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. Moreover, forced expression of Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 also blocked DNA synthesis in WT cyclin D1 transfected cells but not mutant cyclin D1 (T286A) transfected cells (Figure 2C, F, I, and L). Consistent with these findings, we also observed that decreased phospho-Rb protein levels in the cells in which Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1 were co-transfected with WT cyclin D1 but not the mutant cyclin D1 (T286) (Figure 2—figure supplement 2). It was reported that Lysine 269 is essential for cyclin D1 ubiquitination (Barbash et al., 2009). To determine if mutation of Lysine 269 will affect cyclin D1 degradation induced by newly identified E3 ligases in the current study, WT or mutant cyclin D1 (K269R) expression plasmids were co-transfected with Keap1 or DDB2 expression plasmid into HEK293 cells. AMBRA1 expression plasmid, a well known E3 ligase targeting cyclin D1, was used as a control in this experiment. 48 hr after transfection, changes in cyclin D1 protein levels were detected by the western blot analysis. We found that expression of Keap1 or DDB2 in 293 cells reduced WT but not K269R mutant cyclin D1 protein levels (Figure 2—figure supplement 3). To determine if these newly identified E3 ligases directly interact cyclin D1, we performed in vitro ubiquitination assay and used AMBRA1 as a positive control. We found that cyclin D1 ubiquitination ladders were observed when Keap1 or DDB2 were added, suggesting that Keap1 and DDB2 could directly interact with cyclin D1. In contrast, WSB2 only has weak effect to directly interact with cyclin D1 (Figure 2—figure supplement 4).

Our findings indicate that cyclin D1 degradation is mediated by multiple E3 ligases, which are associated with different cullin proteins, including CUL2, -3, -4A, -4B, and -5. Several F-box proteins, Fbxw8, Fbxo4, Fbxo31, and AMBRA1, have previously been reported to mediate cyclin D1 degradation, and these three E3 ligases interact with cullin 1, 4, or 7 (Chaikovsky et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2005; Li et al., 2018; Maiani et al., 2021; Okabe et al., 2006; Santra et al., 2009; Simoneschi et al., 2021). In our study, we found that Keap1 (works together with CUL3), DDB2 (works together with CUL4A and -4B), and WSB2 (works together with CUL2 and -5), which functions as the Ring subunit binding protein interacting with the C-terminal domains of the cullins (Petroski and Deshaies, 2005), participated in the regulation of cyclin D1 proteolysis and affected the cell cycle progression (Figure 2M). The cullins interact with substrate receptor subunits to form ubiquitin ligase complex and mediate cyclin D1 degradation through a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism. This redundant cyclin D1 regulatory mechanism may function to ensure the normal G1-S phase transition and cell cycle progression in the cell.

Compared with transcriptional regulatory mechanism, post-translational regulation controls protein stability and plays a major role in the response to exogenous signals. It has been demonstrated that chemical reagents or γ-irradiation, which induce DNA damage, result in decreased cyclin D1 protein stability (Choo et al., 2009). DDB2 functions as a decisive factor for cell fate after DNA damage. DDB2-deficient cells are resistant to apoptosis in response to a variety of DNA damaging agents and also undergo cell cycle arrest (Stoyanova et al., 2009). Our results raise the possibility that DDB2 may regulate cell cycle pace after DNA damage through regulation of cyclin D1 protein stability.

In addition, cyclin D1 is abnormally up-regulated in many different types of human cancers as a proto-oncogene, including breast, lung, oesophagus, bladder, and lymphoid cancers (Gautschi et al., 2007). Genetic lesions, such as gene amplification or mutations, can only account for a portion of the cases for the abnormal up-regulation of cyclin D1 in these cancers. Growing evidences have shown that defective regulation at the post-translational level may be an important reason resulting in the increased cyclin D1 stability. The half-life of cyclin D1 in normal cells is relatively short (~20 min) due to ubiquitin-proteasome degradation regulated by a number of E3 ligases. In the current study we found that silencing of these ubiquitin ligases resulted in increased stability and accumulation of cyclin D1 in human cancer cells leading to the stimulation of cell cycle progression. In fact, a number of these cullins-associated E3 ligases, such as Fbxo31, Keap1, DDB2, and the cullins, have been demonstrated to function as tumor suppressors or components of tumor suppressor complexes (Fay et al., 2003). These tumor suppressors may exert their functions through controlling the steady-state protein levels of cyclin D1. Loss-of-function mutations of these E3 ligases lead to spontaneous tumor development (Ohta et al., 2008).

Materials and methods

Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, and ubiquitination assay

Request a detailed protocolWestern blotting and immunoprecipitation (IP) were performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2009). The interaction between endogenous cyclin D1 and cullins-associated ligases subunits was determined in HEK293 cells. Proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 μM) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the cell culture 4 hr before cells were harvested for IP or ubiquitination assay. For in vivo ubiquitination assay, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing HA-cyclin D1 or HA-cyclin D1 (T286A) and cullins-associated ligases subunits constructs. Polyubiquitinated cyclin D1 was detected by co-IP using anti-ubiquitin antibody conjugated beads, followed by immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody for cyclin D1. Blots were probed with the following antibodies:

| Antibodies | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclin D1 | Abcam | RRID: AB_2750906 |

| Cyclin B1 | Abcam | RRID: AB_731779 |

| Cyclin A | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | RRID: AB_627334 |

| Phospho-cyclin D1 (Thr286) | Cell Signaling Technology | RRID: AB_2070561 |

| Myc | Sigma-Aldrich | RRID: AB_309725 |

| HA | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | RRID: AB_2894930 |

| Flag | Sigma-Aldrich | RRID: AB_439687 |

| Ubiquitin | Abcam | RRID: AB_2801561 |

| CUL4A | Cell Signaling Technology | RRID: AB_2086563 |

| CUL4B | Proteintech | RRID: AB_2086699 |

| WSB2 | Proteintech | RRID: AB_2216206 |

| Phospho-Rb (Ser780) | Cell Signaling Technology | RRID: AB_10950972 |

Cell cycle analysis

Request a detailed protocolFACS analysis and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay were performed as described before (Santra et al., 2009). For FACS analysis, HCT-116 cells were stably transfected with WT cyclin D1 or mutant (MT) cyclin D1 (T286A). The cells were then transfected with Keap1, WSB2, DDB2, or Rbx1. The cells were harvested 48 hr after the transfection. 16 hr before the harvest, the cells were treated 8 μg/ml of nocodazole (Sigma) for the final 16 hr. As for the non-nocodazole treatment experiments, HCT-116 cells were transiently transfected with siRNA for Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, or Rbx1. 48 hr after the transfection, the cells were synchronized at the G0 phase through serum starvation for over 16 hr. The cells were then stained with propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1 hr. FACS samples were analyzed with a FACSCanto Flow Cytometry System (BD Biosciences). And the data were analyzed using FlowJo 7.6 software according to the manufacturer’s instruction. For labeling with BrdU, HCT-116 cells were stably transfected with WT cyclin D1 or MT cyclin D1 (T286A). The cells were then transiently transfected with Keap1, WSB2, DDB2, or Rbx1. The cells were harvested 48 hr after the transfection. Four hr before the harvest, the cells were treated with BrdU (20 μM).

Cell culture and transfection

Request a detailed protocolHuman colon cancer HCT-116 cells (ATCC, RRID: CVCL_0291) and human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells (ATCC, RRID: CVCL_0045) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C under 5% CO2. The cell lines were tested for mycoplasma-free status before they were used. HCT-116 cells expressing WT HA-cyclin D1 or MT HA-cyclin D1 (T286A) were generated by transient transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Then transfected colonies were selected in the presence of G418 (1000 μg/ml for HCT-116 cells). DNA plasmids were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells in 6 cm culture dishes using Lipofectamine 2000. Empty vector was used to keep the total amount of transfected DNA plasmid constant in each group in all experiments. Flag-EGFP plasmid was co-transfected as an internal control to evaluate transfection efficiency. Western blotting and IP assays were performed 24 hr after transfection.

Plasmids

Myc-CUL3 and FBXW8 were generously provided by Dr. Yue Xiong and Dr. Osamu Tetsu, respectively. Plasmids expressing WT HA-cyclin D1 and MT HA-cyclin D1 (T286A), CUL2, -4A, -4B, -5, and -7, Keap1 and Keap1 delta BTB, DDB2, Rbx1 were purchased from Addgene. The plasmid pCMV6-WSB2 (NM_018639.3) was purchased from OriGene. Loss-of-function MT DDB2 (WD∆238–278), WSB2 (SOCS∆364–400), and Rbx1 (C53A/C56A) were generated using site directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent, CA, USA). All constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

In vivo protein decay assay

Request a detailed protocolCells were seeded in 15 cm culture dishes, cyclin D1 and equal amounts of siRNAs for Keap1, WSB2, DDB2, Rbx1, or control siRNA were transfected, respectively. 24 hr after transfection, cells were trypsinized and split into five 10 cm dishes. 12 hr after recovery, cells were cultured in regular medium with 80 μg/ml cycloheximide (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA), for 0, 30, 60, 120, and 300 min before harvesting. Western blotting was performed to detect the decay of cyclin D1 proteins.

Cullin-associated E3 ligases subunits siRNA library screening

Request a detailed protocol462 unique siRNAs targeting each of 156 genes were coated in 96-well plates (silencer Custom siRNA library, Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). 6xE2F luciferase reporter, cyclin D1 plasmids were co-transfected with the siRNA library into NIH3T3 cells. 24 hr after the transfection, the cell lysates were collected, and luciferase activity was measured using a Promega Dual Luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

Real-time PCR

Request a detailed protocolCell samples were immediately posited in 1 ml TRIZOL (Invitrogen) Reagent after taking out from –80°C refrigerator, and further processed with TissueLyser for RNA extraction. Total cellular RNA was extracted by the TRIZOL Reagent according to the supplier’s instructions. cDNAs of the samples were synthesized with RevertAid First Strand cDNA synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher). And real-time PCR amplification of the cDNAs were performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TAKARA) kit in ABI 7500 real-time PCR system, with following specific primers: cyclin D1 5'-CCGTCCATGCGGAAGATC-3' (upper primer) and 5'-GAAGACCTCCTCCTCGCACT-3' (lower primer); GAPDH, 5'-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGT-3' (upper primer) and 5'-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3 (lower primer). As for the real-time PCR in the gene knockdown experiments, the primers used in this study were as follows: cyclin D1, 5'-CGTGGCCTCTAAGATGAAGG (upper primer) and 3'-CTGGCATTTTGGAGAGGAAG (lower primer); Cul1, 5'-AATGCCCTGGTAATGTCTGC (upper primer) and 3'-GTCACAGTATCGAGCCAGCA (lower primer); Cul2, 5'-CTTACTCCGTGCTGTGTCCA (upper primer) and 3'-GCCTTATCCAACGCACTCAT (lower primer); Cul3, 5'-TCCAGGGCTTATTGGATCTG (upper primer) and 3'-GCCCTTTGACTCCCTTTTTC (lower primer); Cul4A, 5'-AAAGAAGCCACAGACGAGGA (upper primer) and 3'-ATGTCCCTGAACATGCCTTC (lower primer); Cul4B, 5'-CGCCTGTTAGTCGGAAAGAG (upper primer) and 3'-TTCCCGGAACATTCTGATTC (lower primer); Cul5, 5'-TGCAGTCTGTCTTTGGGATG (upper primer) and 3'-TATTGCTGCCCTGTTTACCC (lower primer); Cul7, 5'-TAGAATTGGCCCAGGACTTG (upper primer) and 3'-GCGTCTAGCAGGAGGACATC (lower primer); β-actin, 5'-GGACTTCGAGCAAGAGATGG (upper primer) and 3'-AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG (lower primer). The PCR conditions included a denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, annealing at 58°C for 15 s, and extension at 72°C for 10 s. Detection of the fluorescent product was carried out at the end of the 72°C extension period. The PCR products were subjected to a melting curve analysis, and the data were analyzed and quantified with the Rotor-Gene analysis software. Dynamic tube normalization and noise slope correction were used to remove background fluorescence. Each sample was tested at least in triplicate and repeated using three independent cell preparations.

Luciferase and real-time PCR assays

Request a detailed protocolThe plasmids of reporter constructs were co-transfected with cullins and cyclin D1 expression plasmid into HEK293 cells. 24 hr after transfection, the cell lysates were then collected, and luciferase activity was measured using a Promega Dual Luciferase reporter assay kit.

In vitro ubiquitination assay

Request a detailed protocolThe in vitro ubiquitination assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (ab139467, Abcam, USA). The cyclin D1 fusion protein (P05317, Solarbio, China) expressed in Escherichia coli was incubated at 30°C for the 30 min in the presence of E1, E2, ATP, Ub, and E3 ligase recombinant proteins including Keap1, DDB2, WSB2, RBX1, and AMBRA1 (Abnova, China). Samples were resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis with the anti-cyclin D1 antibody.

Statistics

Statistical comparison between two groups was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test and the two-way ANOVA followed by the Tucky’s post-hoc test (n=3). p<0.05 was considered significant and is denoted in the figures.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files. Source data files have been provided for Figures 1, Figure 2 and the figure supplements.

References

-

ATM is required for rapid degradation of cyclin D1 in response to gamma-irradiationBiochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 378:847–850.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.132

-

BTB protein Keap1 targets antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 for ubiquitination by the Cullin 3-Roc1 ligaseMolecular and Cellular Biology 25:162–171.https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.25.1.162-171.2005

-

Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligasesNature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 6:9–20.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm1547

-

Cyclin D degradation by E3 ligases in cancer progression and treatmentSeminars in Cancer Biology 67:159–170.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.01.012

Decision letter

-

Mei WanReviewing Editor; Johns Hopkins University, United States

-

Detlef WeigelSenior Editor; Max Planck Institute for Biology Tübingen, Germany

-

Chao XieReviewer; University of Rochester Medical Center, United States

Our editorial process produces two outputs: (i) public reviews designed to be posted alongside the preprint for the benefit of readers; (ii) feedback on the manuscript for the authors, including requests for revisions, shown below. We also include an acceptance summary that explains what the editors found interesting or important about the work.

Decision letter after peer review:

Thank you for submitting your article "Multiple Cullin-Associated E3 Ligases Regulate Cyclin D1 Protein Stability" for consideration by eLife. Your article has been reviewed by 3 peer reviewers, and the evaluation has been overseen by a Reviewing Editor and Mone Zaidi as the Senior Editor. The following individual involved in the review of your submission has agreed to reveal their identity: Chao Xie (Reviewer #1).

The reviewers have discussed their reviews with one another, and the Reviewing Editor has drafted this to help you prepare a revised submission.

Essential revisions:

This interesting set of data provides new understanding of the role of cullin-associated E3 ligases in regulating cyclin D1 protein stability. The data within the manuscript largely support most conclusions. However, there are major concerns that need to be addressed.

1) The exact mechanism of how cyclin D1 is ubiquitinated and degraded is incomplete. It is important for the authors to show direct interactions and in vitro ubiquitylation assays. It is also important to put the findings in a coherent model that discusses the existing literature showing that CRL4-AMBRA1 is the major E3 ligase under most tested conditions.

2) It is necessary for the authors to include appropriate controls for the co-IP and CHX chase experiments.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

The lack of identified lysine residue mutant within cyclin D1 that is deficient for ubiquitination is considered a significant weakness for the manuscript.

The in vitro ubiquitination assays of cyclin D1 by different combinations of cullin-E3 ligases will further strengthen the major claim of the manuscript.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

1) One major oversight of the study has been not to include the studies describing CRL4-AMBRA1 as a major E3 ligase degrading cyclin D (1-3) (Simoneschi et al., Nature 2021; Maiani et al., Nature 2021; Chaikovsky et al., Nature 2021). These studies provide convincing evidence that CUL4 and AMBRA1, but not other cullins or substrate adaptors regulate endogenous cyclin D levels in several cell lines including RPE-1, U2OS, and HCT-116 cells, and show functional relevance during human development and cancer. Some of the results presented In these studies contradict the results presented in this short report (e.g. Simoneschi et al. show in Figure 1 that knockdown of only CUL4A/B and AMBRA1, but no other cullin or substrate adaptor, including DDB2, increase cyclin D1 levels in HCT-116 cells). Thus, the authors need to mention these previous findings in their introduction. This would obviously change the scope of their study and require them to address the discrepancies between these previous and their findings and also provide experimental evidence for when and how CRLs other than CRL4-AMBRA1 is important. This would ultimately result in a completely new study.

2) Overstatements:

– The authors claim that no other CRLs than CRL1/7 with substrate adaptors FBXW8, FBXO4, and FBXO31 has been implicated in Cyclin D degradation, which is not the case (see above).

– In the abstract they also claim that KEAP1, DDB2, and WSB2 directly interact with cyclin D1, something they did not test. They only provide evidence that these proteins, when ectopically expressed, can be in a complex with cyclin D1 in cells. These co-IP experiments also lack important controls (see below point 4). Direct interaction can only be claimed by in vitro reconstitution with recombinantly purified proteins.

– Throughout the manuscript effects with RBX1 are presented as novel findings; however, RBX1 is an integral part of all CRLs and thus should be presented as a positive control

3) Another important issue that arises from this study is how different CRLs would recognize cyclin D structurally. The authors draw a model (Figure 2M), in which all four different types of CRLs recognize cyclin D by the same mechanism using different substrate adaptors. This would be rather surprising, given that different substrate adaptors are generally thought to use unique manners to bind specific sets of substrates. Given that the authors do no provide evidence for direct interaction and ubiquitylation, It is equally conceivable that the effects they are observing are occurring through indirect mechanisms and unknown substrates (e.g. AMBRA1).

4) In addition to these major conceptual weaknesses, there are also missing controls for several experiments. To name a few: the anti-substrate adaptor co-IP experiments (Figure 1A-C) are lacking loading controls that show that the same amount of substrate adaptor was enriched in the IP. The ubiquitylation assays (Figure 1E-H) are missing controls that show that the same amount of ubiquitin was immunoprecipitated in each condition. The CHX assays (Figure 1M) need to be quantified and half-lives should be determined.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.80327.sa1Author response

Essential revisions:

This interesting set of data provides new understanding of the role of cullin-associated E3 ligases in regulating cyclin D1 protein stability. The data within the manuscript largely support most conclusions. However, there are major concerns that need to be addressed.

1) The exact mechanism of how cyclin D1 is ubiquitinated and degraded is incomplete. It is important for the authors to show direct interactions and in vitro ubiquitylation assays. It is also important to put the findings in a coherent model that discusses the existing literature showing that CRL4-AMBRA1 is the major E3 ligase under most tested conditions.

In the revised manuscript we have performed in vitro ubiquitination assays and used AMBRA1 as a positive control in this assay. We found that Keap1, DDB2, and WSB2 can induce cyclin D1 ubiquitination. Especially, Keap1-induced cyclin D1 ubiquitination ladder is similar to AMBRA1-induced cyclin D1 ubiquitination ladder. In contrast, no clear ubiquitination ladder was observed in Rbx1 group (Figure 2—figure supplement 4). In addition, we have also added those key publications about the role of CRL4-AMBRA1 in cyclin D1 degradation in the revised manuscript as the reviewer suggested.

2) It is necessary for the authors to include appropriate controls for the co-IP and CHX chase experiments.

We have added ubiquitin input controls for co-IP (Figure 1E-H) and quantified the half-lives for CHX assays (Figure 1N).

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

The lack of identified lysine residue mutant within cyclin D1 that is deficient for ubiquitination is considered a significant weakness for the manuscript.

It was reported that Lysine 269 is essential for cyclin D1 ubiquitination (Barbash et al., 2009). WT or mutant cyclin D1 (K269R) expression plasmids were co-transfected with Keap1, DDB2, or AMBRA1 expression plasmid into HEK293 cells. 48 hours after transfection, changes in cyclin D1 protein levels were detected by the western blot analysis. We found that expression of WT cyclin D1, but not K269R mutant cyclin D1, was decreased in HEK293 cells transfected with Keap1, DDB2, or AMBRA1 plasmid, suggesting that Lysine 269 is essential for cyclin D1 ubiquitination.

The in vitro ubiquitination assays of cyclin D1 by different combinations of cullin-E3 ligases will further strengthen the major claim of the manuscript.

We have performed in vitro ubiquitination assay as the reviewer suggested. The results demonstrated that Keap1, DDB2, or WSB2 can induce cyclin D1 ubiquitination. Especially, Keap1 induced cyclin D1 ubiquitination and formed ubiquitination ladder similar to AMBRA1-induced cyclin D1 ubiquitination ladder. In contrast, no clear ubiquitination ladder was observed in Rbx1 group (Figure S16).

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

1) One major oversight of the study has been not to include the studies describing CRL4-AMBRA1 as a major E3 ligase degrading cyclin D (1-3) (Simoneschi et al., Nature 2021; Maiani et al., Nature 2021; Chaikovsky et al., Nature 2021). These studies provide convincing evidence that CUL4 and AMBRA1, but not other cullins or substrate adaptors regulate endogenous cyclin D levels in several cell lines including RPE-1, U2OS, and HCT-116 cells, and show functional relevance during human development and cancer. Some of the results presented In these studies contradict the results presented in this short report (e.g. Simoneschi et al. show in Figure 1 that knockdown of only CUL4A/B and AMBRA1, but no other cullin or substrate adaptor, including DDB2, increase cyclin D1 levels in HCT-116 cells). Thus, the authors need to mention these previous findings in their introduction. This would obviously change the scope of their study and require them to address the discrepancies between these previous and their findings and also provide experimental evidence for when and how CRLs other than CRL4-AMBRA1 is important. This would ultimately result in a completely new study.

We agree that those findings about CRL4-AMBRA1 in cyclin D1 degradation provide most critical information in the regulation of steady-state protein levels of cyclin D1 in the cell. In addition, we have used CRL4-AMBRA1 as a positive control in our studies during revision of our manuscript.

2) Overstatements:

– The authors claim that no other CRLs than CRL1/7 with substrate adaptors FBXW8, FBXO4, and FBXO31 has been implicated in Cyclin D degradation, which is not the case (see above).

We have added the information about critical role of CRL4-AMBRA1 in regulation of cyclin D1 protein stability in the revised manuscript.

– In the abstract they also claim that KEAP1, DDB2, and WSB2 directly interact with cyclin D1, something they did not test. They only provide evidence that these proteins, when ectopically expressed, can be in a complex with cyclin D1 in cells. These co-IP experiments also lack important controls (see below point 4). Direct interaction can only be claimed by in vitro reconstitution with recombinantly purified proteins.

We have performed experiments to determine if Keap1, DDB2, or WSB2 could directly interact with cyclin D1 and induce cyclin D1 ubiquitination and we found that Keap1, DDB2, and WSB2 can induce cyclin D1 ubiquitination. Especially, Keap1 induced cyclin D1 ubiquitination and formed ubiquitination ladder similar to AMBRA1-induced cyclin D1 ubiquitination ladder. In contrast, no clear ubiquitination ladder was observed in Rbx1 group (Figure 2—figure supplement 4). We also added input control in the co-IP assays as the reviewer suggested.

– Throughout the manuscript effects with RBX1 are presented as novel findings; however, RBX1 is an integral part of all CRLs and thus should be presented as a positive control

We have presented Rbx1 as a control in the revised manuscript as the reviewer suggested.

3) Another important issue that arises from this study is how different CRLs would recognize cyclin D structurally. The authors draw a model (Figure 2M), in which all four different types of CRLs recognize cyclin D by the same mechanism using different substrate adaptors. This would be rather surprising, given that different substrate adaptors are generally thought to use unique manners to bind specific sets of substrates. Given that the authors do no provide evidence for direct interaction and ubiquitylation, It is equally conceivable that the effects they are observing are occurring through indirect mechanisms and unknown substrates (e.g. AMBRA1).

In the revised manuscript, we have performed in vitro ubiquitination assay as the reviewer suggested. Together, with co-IP assay and in vitro ubiquitination assay, our findings suggest that some E3 ligase that we have identified could directly interact with cyclin D1 and some others probably affect cyclin D1 protein stability by indirect mechanisms.

4) In addition to these major conceptual weaknesses, there are also missing controls for several experiments. To name a few: the anti-substrate adaptor co-IP experiments (Figure 1A-C) are lacking loading controls that show that the same amount of substrate adaptor was enriched in the IP. The ubiquitylation assays (Figure 1E-H) are missing controls that show that the same amount of ubiquitin was immunoprecipitated in each condition. The CHX assays (Figure 1M) need to be quantified and half-lives should be determined.

We have added proper controls for co-IP assays and ubiquitination assays and quantified the half-lives for CHX assays in the revised manuscript as the reviewer suggested.

Reference

Barbash, O., Egan, E., Pontano, L.L., Kosak, J., and Diehl, J.A. (2009). Lysine 269 is essential for cyclin D1 ubiquitylation by the SCF(Fbx4/alphaB-crystallin) ligase and subsequent proteasome-dependent degradation. Oncogene 28, 4317-4325.

https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.80327.sa2Article and author information

Author details

Funding

National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB3800800)

- Liping Tong

- Di Chen

National Natural Science Foundation of China (82030067)

- Di Chen

National Natural Science Foundation of China (82161160342)

- Di Chen

National Natural Science Foundation of China (82250710174)

- Di Chen

National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172397)

- Liping Tong

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB3800800) to LT and DC. This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) grants 82030067, 82161160342, 82250710174, and 82172397 to DC and LT.

Senior Editor

- Detlef Weigel, Max Planck Institute for Biology Tübingen, Germany

Reviewing Editor

- Mei Wan, Johns Hopkins University, United States

Reviewer

- Chao Xie, University of Rochester Medical Center, United States

Version history

- Received: May 16, 2022

- Preprint posted: June 1, 2022 (view preprint)

- Accepted: November 8, 2023

- Accepted Manuscript published: November 9, 2023 (version 1)

- Version of Record published: November 15, 2023 (version 2)

Copyright

© 2023, Lu, Zhang et al.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Metrics

-

- 397

- Page views

-

- 107

- Downloads

-

- 0

- Citations

Article citation count generated by polling the highest count across the following sources: Crossref, PubMed Central, Scopus.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as PDF)

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools)

Further reading

-

- Cell Biology

Activating mutations in the leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) cause Parkinson’s disease. LRRK2 phosphorylates a subset of Rab GTPases, particularly Rab10 and Rab8A, and we showed previously that these phosphoRabs play an important role in LRRK2 membrane recruitment and activation (Vides et al., 2022). To learn more about LRRK2 pathway regulation, we carried out an unbiased, CRISPR-based genome-wide screen to identify modifiers of cellular phosphoRab10 levels. A flow cytometry assay was developed to detect changes in phosphoRab10 levels in pools of mouse NIH-3T3 cells harboring unique CRISPR guide sequences. Multiple negative and positive regulators were identified; surprisingly, knockout of the Rab12 gene was especially effective in decreasing phosphoRab10 levels in multiple cell types and knockout mouse tissues. Rab-driven increases in phosphoRab10 were specific for Rab12, LRRK2-dependent and PPM1H phosphatase-reversible, and did not require Rab12 phosphorylation; they were seen with wild type and pathogenic G2019S and R1441C LRRK2. As expected for a protein that regulates LRRK2 activity, Rab12 also influenced primary cilia formation. AlphaFold modeling revealed a novel Rab12 binding site in the LRRK2 Armadillo domain, and we show that residues predicted to be essential for Rab12 interaction at this site influence phosphoRab10 and phosphoRab12 levels in a manner distinct from Rab29 activation of LRRK2. Our data show that Rab12 binding to a new site in the LRRK2 Armadillo domain activates LRRK2 kinase for Rab phosphorylation and could serve as a new therapeutic target for a novel class of LRRK2 inhibitors that do not target the kinase domain.

-

- Cell Biology

The MRTF–SRF pathway has been extensively studied for its crucial role in driving the expression of a large number of genes involved in actin cytoskeleton of various cell types. However, the specific contribution of MRTF–SRF in hair cells remains unknown. In this study, we showed that hair cell-specific deletion of Srf or Mrtfb, but not Mrtfa, leads to similar defects in the development of stereocilia dimensions and the maintenance of cuticular plate integrity. We used fluorescence-activated cell sorting-based hair cell RNA-Seq analysis to investigate the mechanistic underpinnings of the changes observed in Srf and Mrtfb mutants, respectively. Interestingly, the transcriptome analysis revealed distinct profiles of genes regulated by Srf and Mrtfb, suggesting different transcriptional regulation mechanisms of actin cytoskeleton activities mediated by Srf and Mrtfb. Exogenous delivery of calponin 2 using Adeno-associated virus transduction in Srf mutants partially rescued the impairments of stereocilia dimensions and the F-actin intensity of cuticular plate, suggesting the involvement of Cnn2, as an Srf downstream target, in regulating the hair bundle morphology and cuticular plate actin cytoskeleton organization. Our study uncovers, for the first time, the unexpected differential transcriptional regulation of actin cytoskeleton mediated by Srf and Mrtfb in hair cells, and also demonstrates the critical role of SRF–CNN2 in modulating actin dynamics of the stereocilia and cuticular plate, providing new insights into the molecular mechanism underlying hair cell development and maintenance.